seasons are changing — issue #54

Coming from tropical Singapore, where it’s pretty much hot all year round, spring was never something I resonated with. It didn’t rouse in me feelings people associate with the end of winter: hope, joy, and revival. At most, I’d think of the fleeting beauty of Japanese sakura, or cherry blossoms, and the vibrancy of Holi celebrations in India and Nepal.

It was not just that I had little concept of the seasons. For most of my life, my routines and occupations were never influenced by the natural cycles (and limits) of time. Compared to my ancestors, whose lifestyles were more guided by nature, how I spent my time was instead shaped by how productive I could be. Oblivious to the dark sky, I spent my youth trying to lengthen the night: scrolling through my phone, meeting friends, bingeing a Netflix series, or rushing a deadline.

If not for the five daily Islamic prayers—their timings based on the sun’s position in the sky—I would move through my days untethered from nature’s rhythms. As a kid, my parents would warn me to “balik sebelum Maghrib (come home before the dusk prayer),” or sleep early so I could wake up for Fajr (the dawn prayer). Other than Ramadan—a holy month in the Islamic calendar—how I lived and what I consumed depended little on what month it was. Until recently, only January and December were for me a beginning and an end, not knowing that there existed other meaningful ways to organise time.

In this article by Camilla Power, she writes that the Gregorian calendar represents the colonial control of time, where native systems of cyclical time were replaced by ideas of “time being ‘wasted’ or ‘spent’, that time was indeed ‘money’.” According to Power, this paved the way for the prevailing imperial order, which came with the spread of industrial capitalism. Economic exploitation, especially of low-wage workers, became entrenched in our global system as the value of human labour became attached to how much a person could produce.

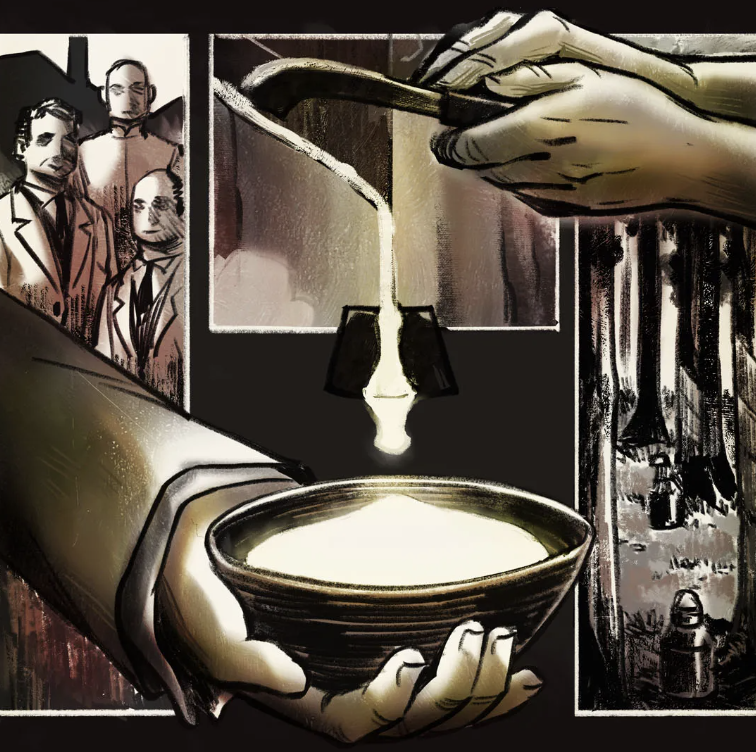

Since the Spring of Nations, or the Revolutions of 1848 in Europe, spring has been attached to other mass movements toward democracy and political freedom. Worker’s rights laid the groundwork for these protests, as it did in Myanmar’s 2021 Spring Revolution. A year before, the revolutionary Burmese anthem, “Thway Thitsar” was sung by workers fighting for higher wages outside a shoe factory.

Like I said, I’ve never been attuned to the natural turnings of time. But as more people around the world rise up against unjust systems, I feel the seasons changing. This spring, I am hopeful.

Apologies: We got a little too excited last week and accidentally sent out an email about our Lapis launch to all notes from the equator subscribers. Please do read the article, but just know that we won’t be blasting out emails like that (to all 2,054 of you! 😅) in the future.

more from us...

As corporate pressure and new laws push seed-saving to the margins, Asia’s farmers fight back to reclaim their crops.

How did the colonial administration in 20th century Malaya exploit labour to control the booming rubber trade?

BTS

Working on a microstory about different Asian new years made our Editorial Lead Nabilah question how she thought about time. While it’s a fact that we follow the Gregorian calendar, she never quite realised just how much this one specific calendar has shaped her perception of time. Read more about the process of putting this story together.

Stuff we love

↗ Explore the archive of global working class histories in this map.

↗ Discover the 24 terms of the Chinese solar calendar, rooted in ancient traditions.

Did you know?

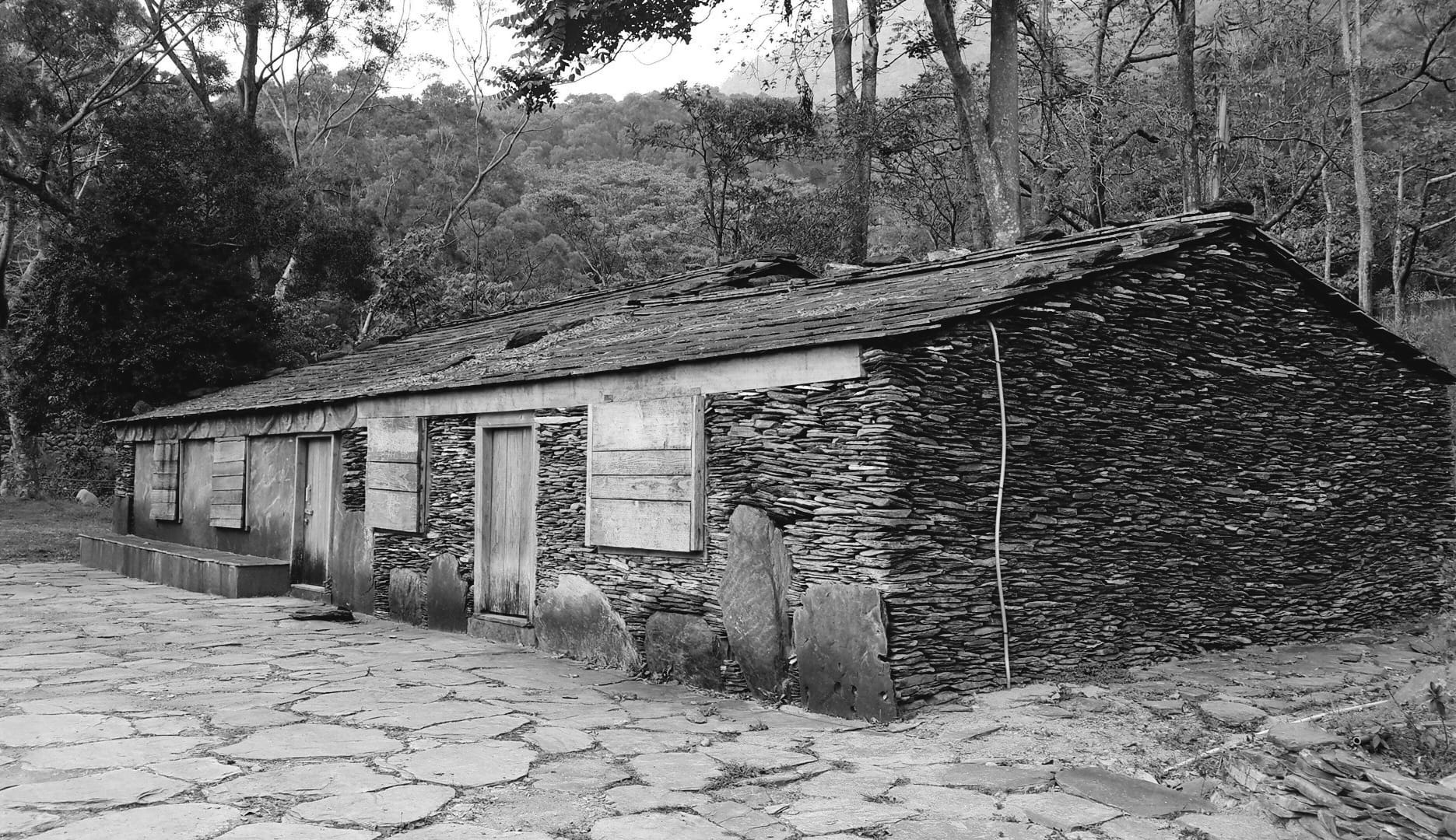

Ballad of the Forest Workers

Ballad of the Forest Workers

I was sent to Valulju, but Yamanonaka is where I was born.

I want to go home, I want to see my family again.

I will take route no. 11 and I will follow it to the end,

I want to go home, I want to see my family again.

In the 1960s, Taiwan's National Forestry Department faced a labour shortage, leading indigenous farmers to take up forest work in remote mountainous areas. Living in makeshift camps, they passed time around campfires, singing and playing guitar. This led to the birth of "The Ballad of the Forest Workers", which they sang in Paiwan language, expressing longing for loved ones left behind. The song offered solace amid their gruelling conditions, and lyrics were improvised to reflect their individual experiences of hardship and separation. The above verses were composed by a woodcutter who longed to return to his home and family.