What Rivers Remind Us Of— issue #66

Indigeneity teaches us memory, and like rivers, carries us back to the contested places we call home, their interconnections, and the responsibilities they demand.

For many of us who grew up in Singapore, August brings the familiar sight of red-and-white flags draped across our public housing estates and neighbourhoods. There’s also the inevitable rotation of National Day songs: each year a new anthem of patriotism, marking what sets us apart from other countries. One of the most enduring is Kit Chan’s Home. The line “There's a place that will stay within me/ Where that river always flows” has become almost mythic, a shorthand for the uniqueness of Singapore. Yet rivers, seas, and water have never only marked our singularity, they’ve always been the source of our interconnection, our responsibilities to one another, and to the world.

I grew up next to Jurong Lake Gardens, thinking of the water there simply as a lake. I didn’t know then that it was once part of Sungei Jurong, a river and region once significant to Orang Laut communities. At its mouth lay Pulau Samulun, now host to Jurong Shipyard. Even its name carries an important clue: Samulun comes from Sembulun, one of the groups from the Orang Laut community. My memory of the place was initially small, contained: just a neighbourhood park that seemed permanent, inevitable. It took a friend reminding me of its histories to realise how much I had forgotten, how easily erasure embeds itself into the landscape and into us.

In our work with Orang Laut Singapore, I've come to see that Singapore was never just a single island. We are an archipelago of seventy-seven, connected by water to other parts of the region such as Riau and the Southern islands. This 9 August as we celebrate both Singapore's independence and the International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples, it reminds me that Singapore is full of fragile, contested memories. As we celebrate Singapore's achievements, we also inherit the losses that Indigenous people experienced. These losses are ours too, and they continue to reverberate through our nation as we deal with calamities of the present: climate change, social divisions, and inequality. To remember is to refuse those silos, to recognise that the waters around us bind as much as they divide. Memory falters, but water insists: we are interconnected. Nothing reminds me more of this than flotillas that are trying to break the blockade of Gaza, where indigenous Palestinians are resisting and safeguarding their own landscapes and memory.

Walking now by the waters of my childhood, I think about what is missing, what has been buried, and what still flows beneath. Indigeneity reminds us not only of our smallness, but also of our vastness, our ties across seas and borders, and therefore our responsibilities to the world. Remembering is imperfect, ongoing work. But memory, like rivers, has the power to return us home.

more from us...

As tourists, can we support Indigenous communities without perpetuating colonial narratives?

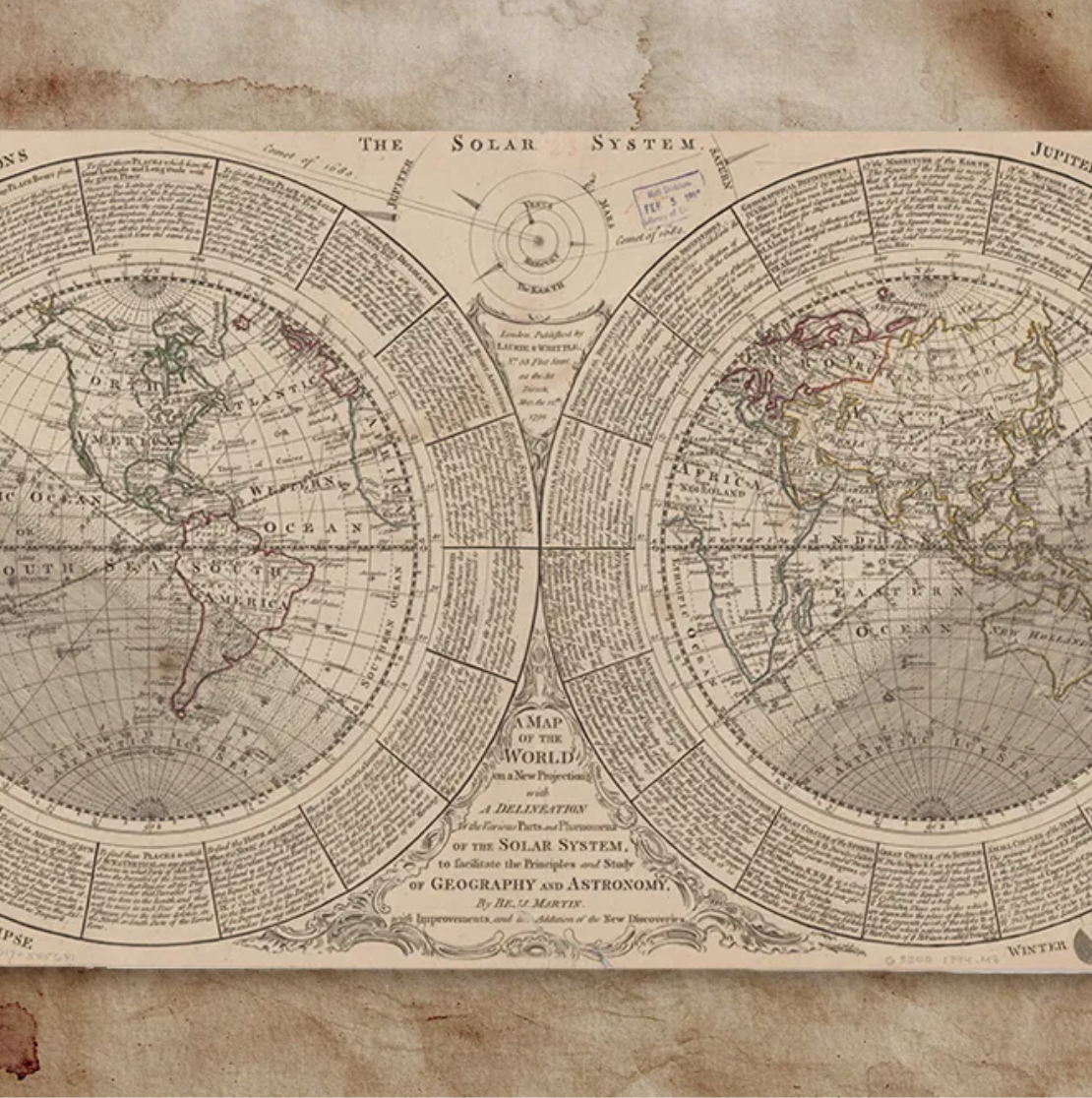

Maps make it seem like the world has always been “as it is”, but to what extent is this true?

Kawan special

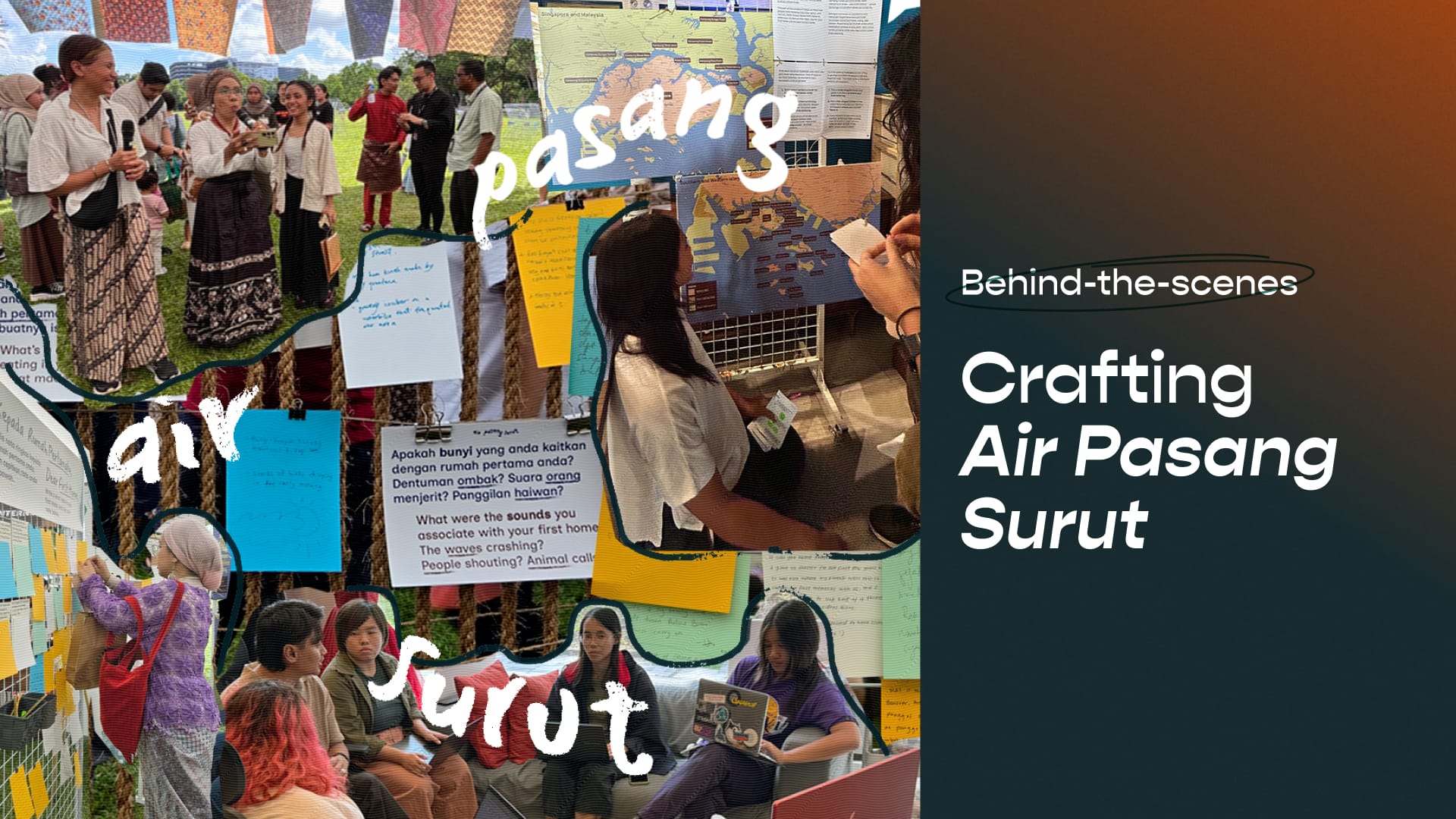

On June 14, Kontinentalist hosted an exhibit titled “Air Pasang Surut” as part of Hari Orang Pulau (Islanders’ Day) at West Coast Park, Singapore. Co-designed with Orang Laut Singapore, the participatory exhibit gathered thoughts and memories surrounding home and displacement, while creating space for shared reflection among islander communities and mainlanders. In this article, the team shares how they drew inspiration from Indigenous frameworks and participatory mapping projects to craft a data project with care and intentionality.

Stuff we love

↗ Speakers of Guugu Yimithirr, an Aboriginal language in Far North Queensland, Australia, have a strong spatial awareness that keeps them oriented indoors or blindfolded, akin to having an internal compass that relies on cardinal directions.

↗ The Indigenous Malaysian dialect of Jahai, spoken in Perak, has diverse words to describe precise scents, like “plaheng” which refer to the the odours of crushed headlice or squirrel’s blood.

↗ Indigenous communities in Borneo are adopting mapping tech like the Jaga Tanah app to resist the expansion of plantations and determine rights to their land.

↗ Explore Ainu Neno An Ainu, which collects the stories of the Ainu, the Indigenous population of northern Japan.

Did you know?

Bagai santan dengan gulanya

Bagai santan dengan gulanya

“Bagai santan dan gulanya” or “like coconut cream with its sugar” is a Malay proverb used to describe elements of perfect compatibility. The culinary pairing of santan (coconut cream) and gula (sugar) is seen as a match made in heaven. Native to coastal regions including Southeast Asia, these ingredients are commonly found in sweetmeats and creamy desserts from the Malay world. In Kitab Kiliran Budi, a book of Malay proverbs, the entry "manis laksana gula serawa", meaning “as sweet as coconut-creamed sugar”, illustrates how this combination is a simile for sweetness and compatibility.

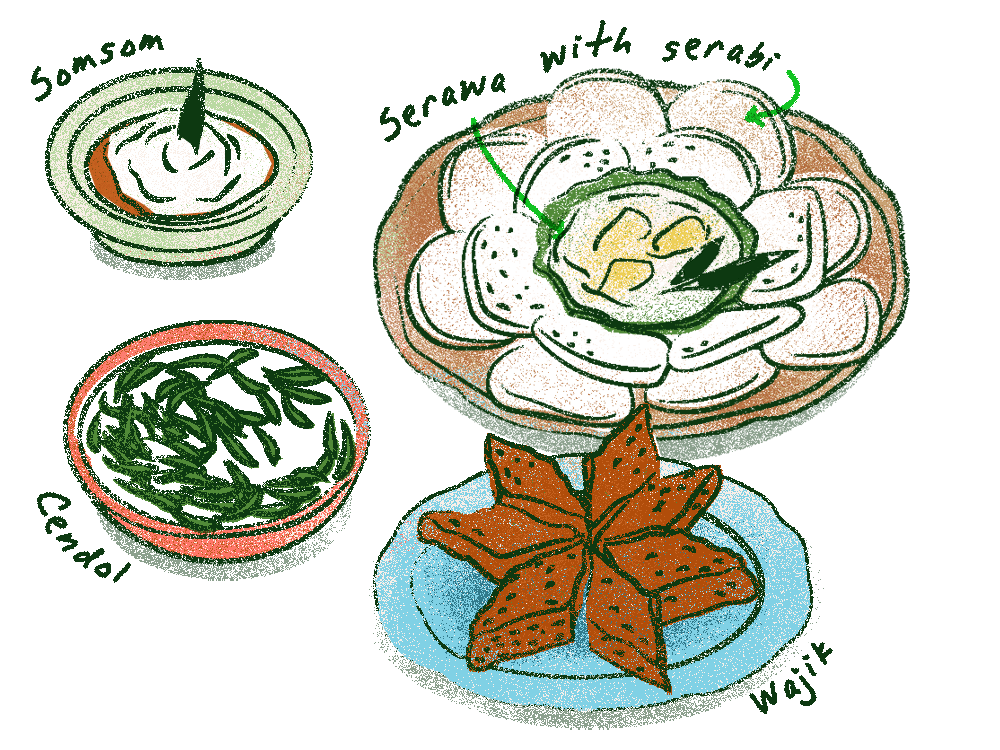

Examples of santan and palm sugar-based desserts:

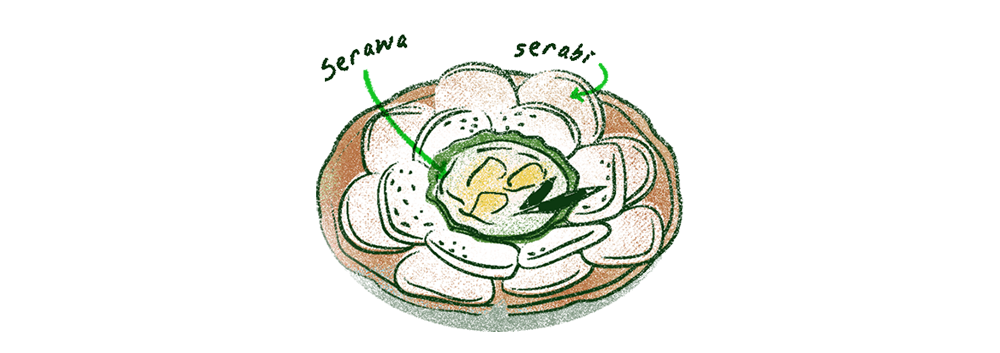

1. Serawa with serabi

A type of sweet sauce typically made from durian pulp, coconut cream, and palm sugar. It can be eaten with serabi, a type of pancake made with coconut milk and rice flour.

2. Cendol/Dawet/Bánh lọt/Lot chong/Mont let saung/Lod song

A sweet icy dessert consisting of pandan-flavoured rice flour jelly, coconut cream, and palm sugar syrup. Its variations across Southeast Asia have toppings like red bean, durian, and corn.

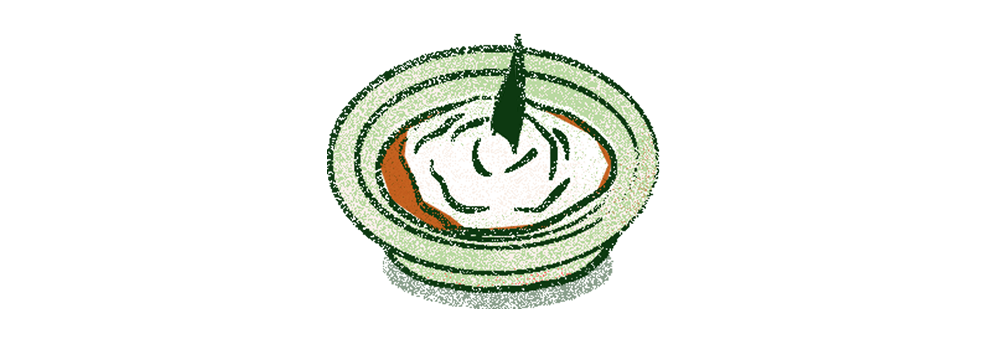

3. Somsom

A type of pudding made with rice flour and coconut milk, often served with palm sugar syrup.

4. Wajik

Glutinous rice cooked with palm sugar and coconut cream, typically cut into a diamond shape.