Unlearning what we know — issue #58

“I have learned the names of all the bushes, but I have yet to learn their songs.” These past months, the Kontinentalist team has been deep in learning and reflection. We started our “Decolonial Reading Club”: bi-monthly sessions breaking down coloniality, knowledge, and being. This quote from Braiding Sweetgrass, recounting an Indigenous person’s perspective to botany, brought several of us to tears.

I recently also visited the home of Carl Linnaeus, famed for being the “father of modern taxonomy” and Systemae Naturae. As I walked through his cottage, I overwhelmingly thought to myself: so much of what he achieved and possessed was only possible because of Europe’s colonial encounters with the “East”, or Asia. The materials he studied were brought to him from European expeditions to Asia and South America. The chintz that the women in his family used for their dresses, the porcelain and silver that adorned their dining tables, the curiosities that inspired his worldly disposition. Colonisation and scientific knowledge operated hand-in-hand.

Linnaeus’ imprint is felt on every aspect of our understanding of the natural world. Flora and fauna that have been categorised, sorted, and renamed in Latin. It’s not that his system is wrong or inaccurate, but it is imperfect; incomplete. It ignores other knowledge systems, especially Indigenous ones that have been developed over centuries. Scientific knowledge made in the wake of colonisation is without song, stripping down our beautiful world only to its functions and practicalities. In place of their historic, local names are “scientific” ones that most find impossible to even pronounce. Knowledge production and documentation can also be a form of erasure.

Data is no different. Life is filtered through columns, rows, numbers, and curated categories. These narrow views inform our everyday life, influencing policies, economies, and status. For our team, these revelations have been difficult, but instead of discarding and rejecting them, we’re formulating what we think makes sense. We’re unlearning everything we know of education, systems, and life as we know it, but also piecing together a method of working and collaborating led by repair, beauty, and love.

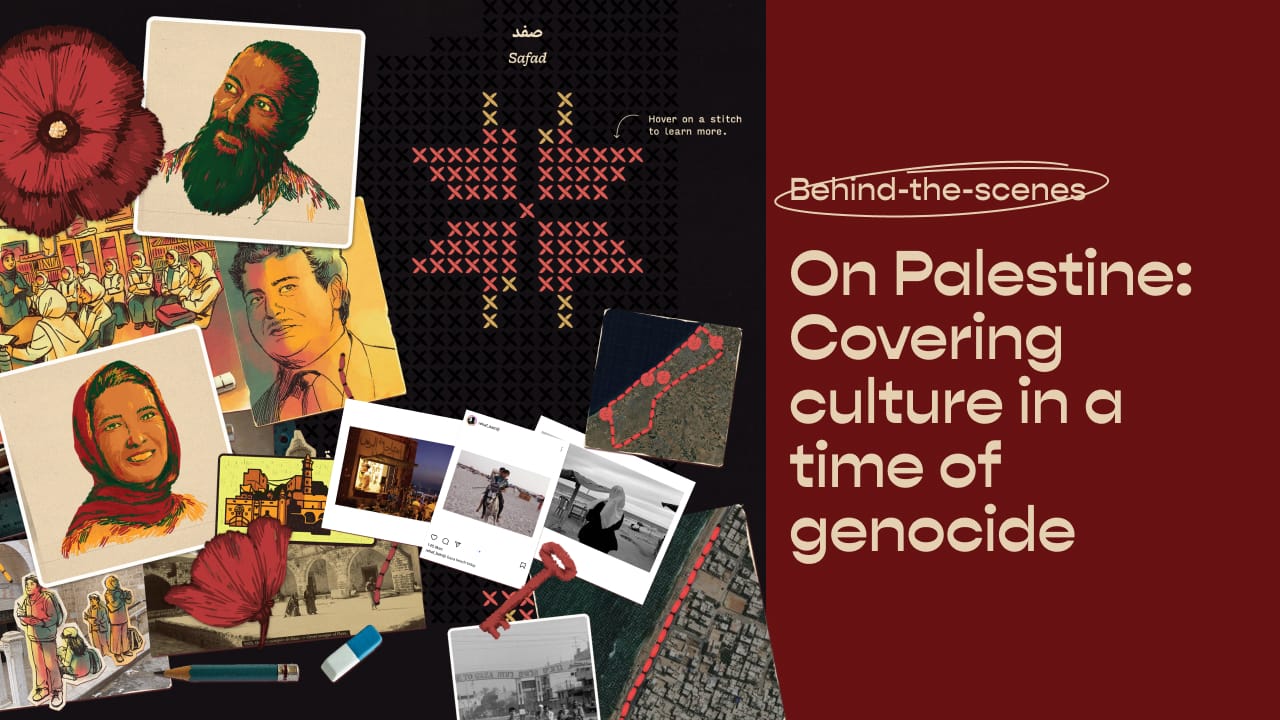

That is what our latest story on Gaza is about. My colleagues have laboured over this piece for a year, and while that effort should not be underestimated, it really pales in light of the horror Palestians face daily. In confronting and unpacking coloniality, we must remember not only to fixate on pain and wound. It is our hope that our story can help others see the life, culture, and beauty of Gaza. Genocide isn’t just about violence on physical bodies, but the decimation of everything that makes us human.

more from us...

Horror films are a hit in Indonesia, but what do they reveal about society’s perceptions of women?

How are Singapore’s indigenous sea-faring communities reclaiming their narratives?

Kawan Special

What does Gaza require from those who bear witness? The team behind our latest story on Palestine shares their process, thoughts, and feelings while highlighting the beauty of life in Gaza amid the profound loss of Palestinian heritage and cultural identity.

Stuff we love

↗ Palestinian Sound Archive brings you a collection of digitised music from Palestine, celebrating Palestinian culture, heritage, and resistance.

↗ Mosques across China are being demolished and modified, slowly erasing the culture of its Muslim communities.

↗ Decolonizing Southeast Asian Sound Archives works to produce open access collections of regional music stored in colonial repositories.

↗ Mehelle is a digital mapping project from Ajam Media Collective preserving the sights, sounds, and memories of neighbourhoods from Central Asia to the Caucasus.

Did you know?

Reconciling indigenous rituals and new religions

Reconciling indigenous rituals and new religions

Many Indigenous rituals in Southeast Asia were syncretised with the arrival of religions like Christianity and Islam. Conversions to these Abrahamic faiths did not stop people from practising their traditions, instead incorporating them into their new religions.

In Sabah, Malaysia, and other parts of the region, the Indigenous Kadazan-Dusun people carry out a series of death rites, such as the Momisok and Papaakan ritual. The Momisok ritual, meaning to switch the lights off, is a ritual where all the lights in the houses are turned off to observe darkness. The Papaakan ritual, meaning to offer a meal, is a practice where they perform an invitation for the spirits of the deceased to feast on offerings served on a table. These practices were believed to be the last avenue for the deceased and the living family members to communicate before going into the next realm. Instead of the traditional servings of food and wine, the community uses portraits of the deceased, crucifixes, and rosary beads as symbols of their Christian faith.