The stories behind the missing: Reporting on enforced disappearances in Balochistan

Our latest piece, written by freelance journalist Somaiyah Hafeez, highlights the silent epidemic of enforced disappearances in Balochistan. A stealthy, routine occurrence across Pakistan, disappearances are particularly rife in the country’s marginalised province. In this inside look at the story, Somaiyah shares her experiences covering this issue as a local reporter, and how she worked with our writer Zafirah to tell the story behind the numbers.

Somaiyah: The late Pakistani journalist Sajid Hussain, who extensively wrote on the issue of enforced disappearances, said “the dead don't haunt me as much as missing do.” Like Sajid, the missing persons from Balochistan have increasingly started to haunt me as a journalist. Since I started journalism, it is an issue I have remained focused on, however only now has it become ghastly to me. This happened as I spent time with the Baloch women protesting for a month in Islamabad against enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings. When I was arrested along with these protestors on 21 December 2023 as I was covering the protest outside the National Press Club (NPC) in Islamabad, my family couldn’t bear those few hours not knowing my whereabouts. It is unimaginable what decades of this uncertainty must have done to the missing persons’ families.

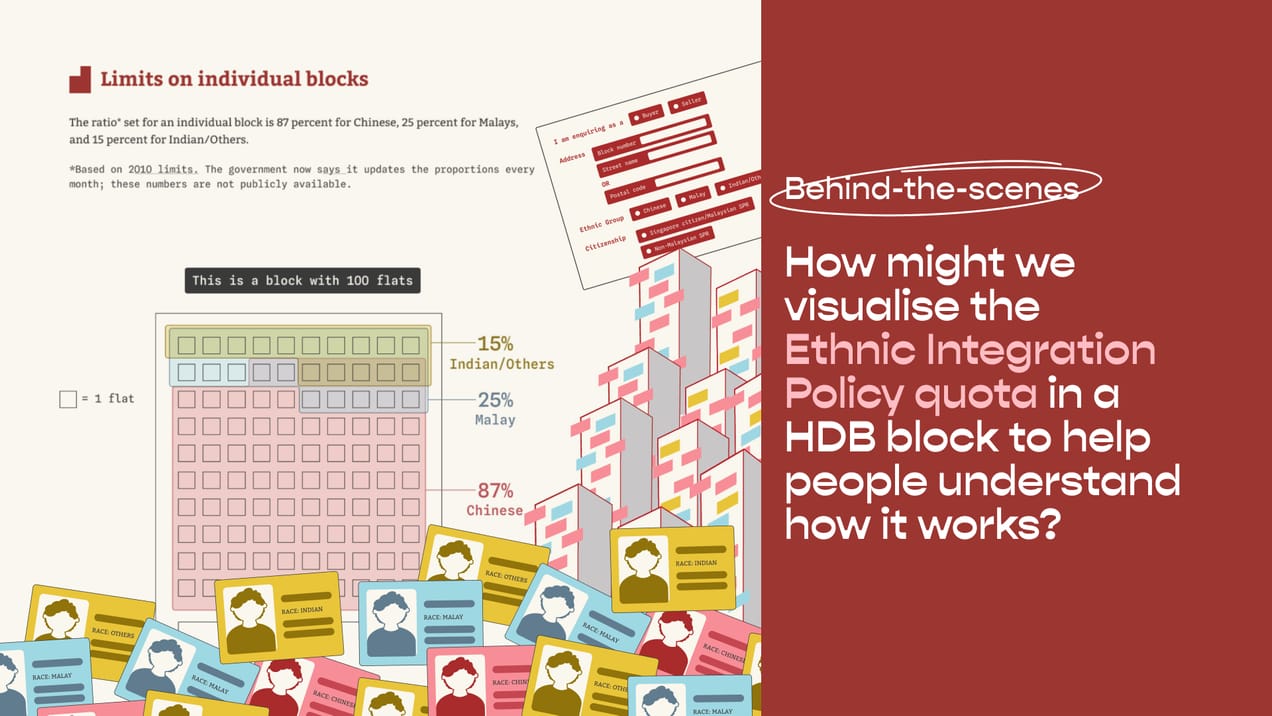

Zafirah: Before Somaiyah pitched this story to us, I was unaware of the conflict in Balochistan and how rampant enforced disappearances were in the region. Kontinentalist had worked on a similar story on the forcibly disappeared in Mexico a few years back, but I did not know that such disappearances could take on various forms, and were a persistent problem across Asia, most notably in Pakistan.

As discussed in the story, enforced disappearances are used by states to silence, terrorise, and oppress dissidents. Due to the fear of retaliation or state control over the media, mainstream outlets often do not report enforced disappearances, or give an accurate picture of the problem. Without local human rights organisations, activists, and independent journalists like Somaiyah, enforced disappearances would happen in silence. I was privileged to work with her, a reporter from Balochistan with years of experience reporting on this issue.

Somaiyah: Before working on this data-driven story, I hadn’t realised how important it was to have proper data and documentation counter obstacles such as the authority’s underreporting of cases of enforced disappearances. There is a lack of concrete data collection for multiple reasons: the fear of repercussions for activists, difficulty accessing remote areas in Balochistan, and the government simply not allowing human rights organisations to work freely on the ground. This has made it easy for the government to shun this huge issue.

Zafirah: For this story, my job involved helping Somaiyah sift through the various data she collected from local non-profits documenting the issue in Balochistan, and the Commission of Inquiry, which was set up by the government to address complaints and investigate those cases. The main problem we faced, which was highlighted in the story, was that there was no accurate or reliable number of enforced disappearances in Balochistan. Data from each organisation differed, while official numbers seemed way too low.

Unable to draw meaningful comparisons between the different datasets, or sufficiently support them with accounts from Somaiyah’s interviewees, I focused on showing how a significant number of cases reported to the Commission were discarded. After initially experimenting with a Sankey diagram and a small multiples chart, I chose to go with a basic bar chart to present this data.