the power of play— issue #64

My childhood was distinctly marked by improvisation. In the days before screens and social media, we played masak-masak and make-believe, using the everyday things around us to bring our imaginary worlds to life. The corridors of our HDB block became a makeshift supermarket aisle, a blanket transformed into a fort, and the sacks of rice at my mother’s provision store were pillows for my midday nap.

When it was just me and my imagination, the sky was the limit. Some days I was a scientist, collecting and analysing plant specimens around my neighbourhood, or a teacher lecturing on the day’s homework (my poor aunty had to be my pretend student). Other days I sold kacang puteh, dishing out make-belief peanuts rolled in old newspapers, or I was an explorer on my bicycle. I often attribute my ability to improvise on the fly to the freedom and independence my parents gave me as a child.

Recently, Kontinentalist has been busy with our studio projects, one of which is supporting Playeum, a charity that advocates for the transformative power of play—how it fosters creativity, nurtures emotional intelligence, and cultivates a sense of agency in children. Playeum creates inclusive spaces and programmes where all children, especially those from marginalised backgrounds or with disabilities, can express themselves freely and discover their strengths. All this, with the hope that play can provide them with a greater defence against the stresses of adulthood.

But not every child has access to safety, play, and joy. Research has shown that prolonged stress from socio-economic inequalities can have long-lasting effects on mental and physical health. Then there is the Glasgow effect, in which Glaswegians were found to have had poorer health and higher premature mortality rates than the rest of Scotland and the UK despite living in a wealthy country. One key contributor? Chronic stress, which wears down our body’s critical physiological responses—our “fight or flight” systems—over time, and often starts in childhood.

This is why play isn’t just a luxury or frivolity—it’s a right. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child recognises every child’s right to rest, leisure, and play. Play empowers children to understand their world, develop a sense of belonging, and most importantly, to be seen and heard. But don't take our word for it—read what 201 young children in Singapore say matters most to them and will make a difference in Playeum's latest report. In tribute to International Day of Play which fell on 11 June, we urge you to remember your childhood selves, and think about how you'd want to reimagine a better world for our children—and for ourselves.

We hope to see you there!

more from us...

Remember the McDonald’s Hello Kitty craze in the 2000s? What other things have Singaporeans queued for?

In many cultures, board games have long been a source of entertainment and competition. What are some common ones in Asia?

Kawan special

For many of us who grew up in the ‘90s, snacks like Mamee noodles, Milo nuggets, haw flakes, and iced gem biscuits bring back colourful memories and the nostalgic taste of childhood. In this Kawan article, Kontinentalist intern Ananaya Mittal brings us down memory lane by exploring the visual language of our favourite old-school treats.

Stuff we love

↗ If school sucked for you, you’re not alone. This story by The Pudding used a survey of middle-school kids to show how school affected their sense of belonging.

↗ Ah, the good old days. Gamemaker Aidan Strong revisits childhood crazes and phases.

↗ Can data viz help with homework? Data artist Julia Krolick introduces data viz to her son through everyday projects.

↗ How did data journalist Alvin Chang recreate his favourite childhood dish, his grandmother's kimchi?

Did you know?

The popular game of strategy

The popular game of strategy

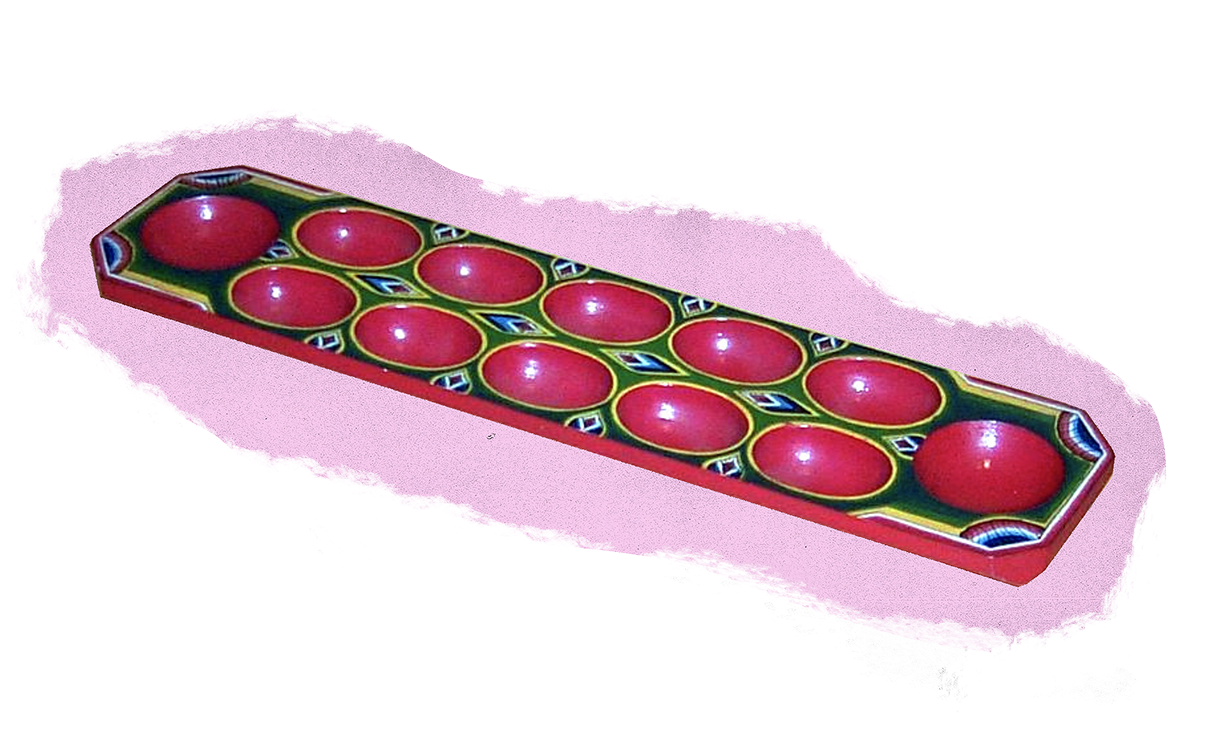

Congkak is a popular game in Southeast Asia which requires two players to move small marbles or seeds around a board via rows of holes. The goal is to accumulate the most number of game pieces in the large holes at the end, known to some as “storehouses”. In the Malay archipelago, the smaller holes were known as “kampong”, or village houses.

The game originates from the Arabian region, where it is known as “mancala”, or “to move”. It has different variations across Asia, Africa, and the Americas, mainly in terms of materials, design, and social settings. Boards might be carved from wood, drawn in sand, or made of stone or metal. Game pieces range from seeds and pebbles to shells and beads. In Indonesia, they might use cowrie shells, and boards are intricately carved to reflect the symbolic motifs of specific ethnic groups. In parts of the Malay archipelago, the game is played by women on the open verandahs of their kampong houses, turning gameplay into a communal, social activity.