no better way to make sambal — issue #63

Ever since I can remember, the first day of Syawal, or Hari Raya, was not complete without a steaming, spicy bowl of kuah chelok in my late grandmother’s house. The traditional tangy soup was closely linked to our Boyan heritage, a word derived from Bawean Island in East Java, where my ancestors originated from. My cousins and I, about 20 of us, would eagerly wait in a line that stretched from the kitchen to the living room to pour the soup (usually served with ikan tongkol, tuna) over piping hot rice. Already fiery enough to induce tears, the dish was incomplete without adding a dollop of sambal belacan.

I didn’t always know what it meant to be Boyan, but our elders made sure we all knew how to eat like one. Another childhood favourite was roti boyan, a pan-fried pastry filled with egg, onion, and mashed potato. After my grandmother’s passing, it was no longer a feature at family gatherings. Even if one knew the recipe, it was cumbersome to prepare the dough. Faced with the prospect of not having authentic, homemade roti boyan ever again, I messaged my eldest cousin, who had grown up watching our grandmother make it from scratch: “Please teach me!”

It wasn’t just my stomach speaking. There was a desire to preserve my grandmother’s memory, and connect to my family’s heritage. Humans form strong memories around food; indeed the only Baweanese words I recall revolve around it. I learnt later that the Baweanese have their own language and culture, distinct from the larger Malay community in Singapore. We had a close relationship with the sea, and I recall how much my grandmother loved being at the beach. I longed to know more about what nourished the generations before me. This feeling only grew stronger as years passed and traditions started fading away.

I now live abroad with my own family, and I make sure to carry some staples that would give me a taste of home: belacan (shrimp paste), daun pandan (pandan leaves), daun limau purut (kaffir lime leaves), and serai (lemongrass). When we were looking for a place to stay in Cairo, we found a used batu lesung (traditional Malay mortar and pestle) in the kitchen of a Malaysian-owned flat. It was enough to seal the deal. There was just no better way to make sambal. Preparing food the way my elders did links me back to my roots.

This is why our latest story on nature’s utensils, written by Taahira Ayoob, resonates deeply with me. By relating her experiences cooking with women in Sri Lanka, she rekindles the magic of slow and communal cooking with traditional tools. It reminds me of the deftness of my mother’s hands at the chopping board, the warmth of family gathering to weave ketupat (rice cake wrappers woven from coconut or palm leaves) on the floor, and the sound of batu lesung pounding in the kitchen—the promise of something delicious.

I’ve come to learn that the tools, rituals, and recipes passed down from our elders embody the wisdom of the past, inviting us to slow down, and appreciate the gifts of nature and tradition.

Do you have heirloom dishes or tools still beloved in your family? Hit reply, we’d love to hear from you.

Announcement

Kontinentalist recently unveiled The Hidden Green, a 6x12 metre artwork and data storytelling project commissioned by Singapore Art Museum. We used data on Singapore’s roadside trees to reveal our relationship to nature, and what gets obscured by data. The work, which includes maps, narratives, poetry, leaves and tree rubbings, invites people to reflect on nature in a more reparative way.

If you’re in Singapore, check it out right outside the museum’s entrance at Tanjong Pagar Distripark!

more from us...

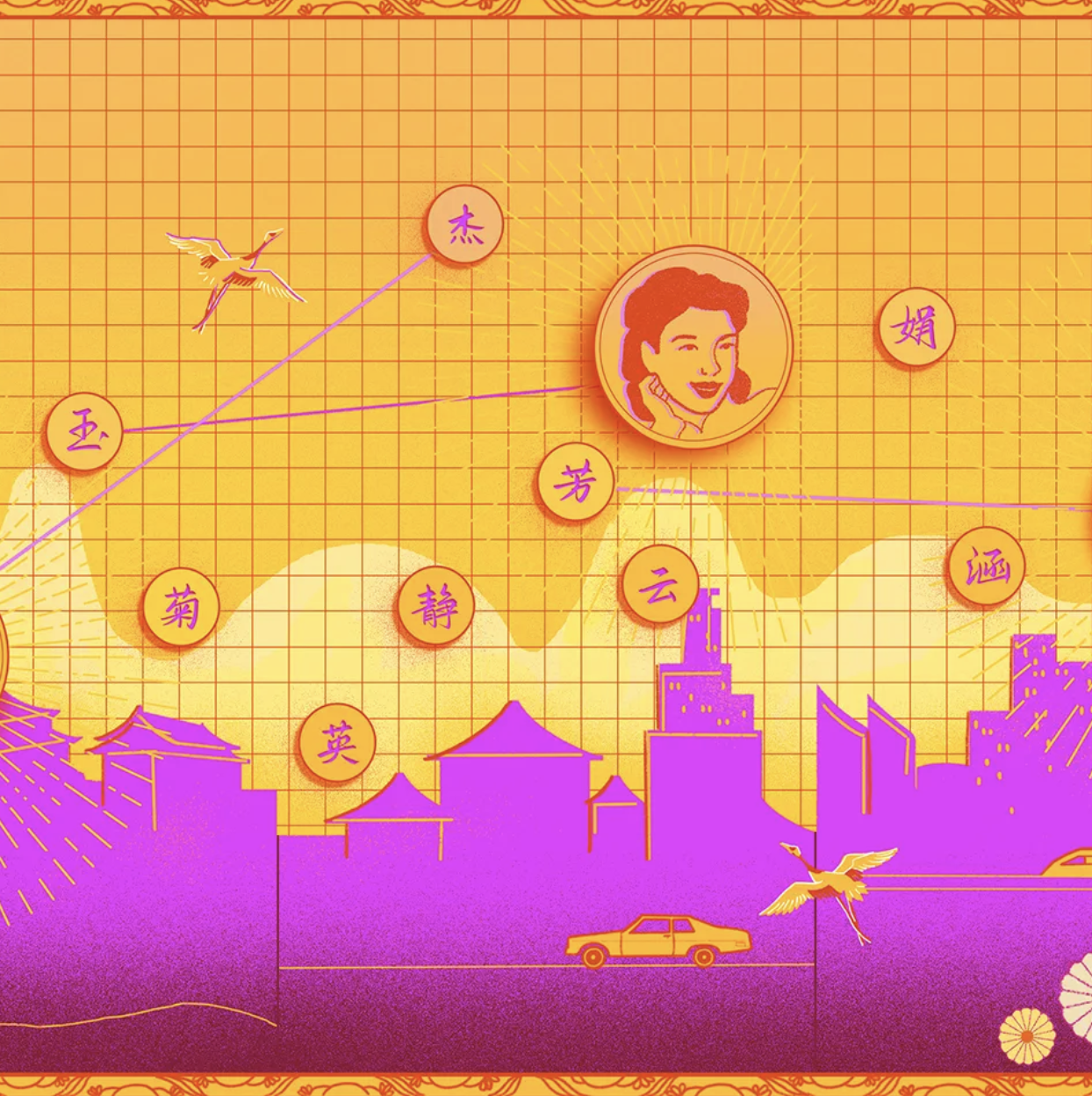

What do Han Chinese names tell us about the history of a nation and its people's hopes for the future?

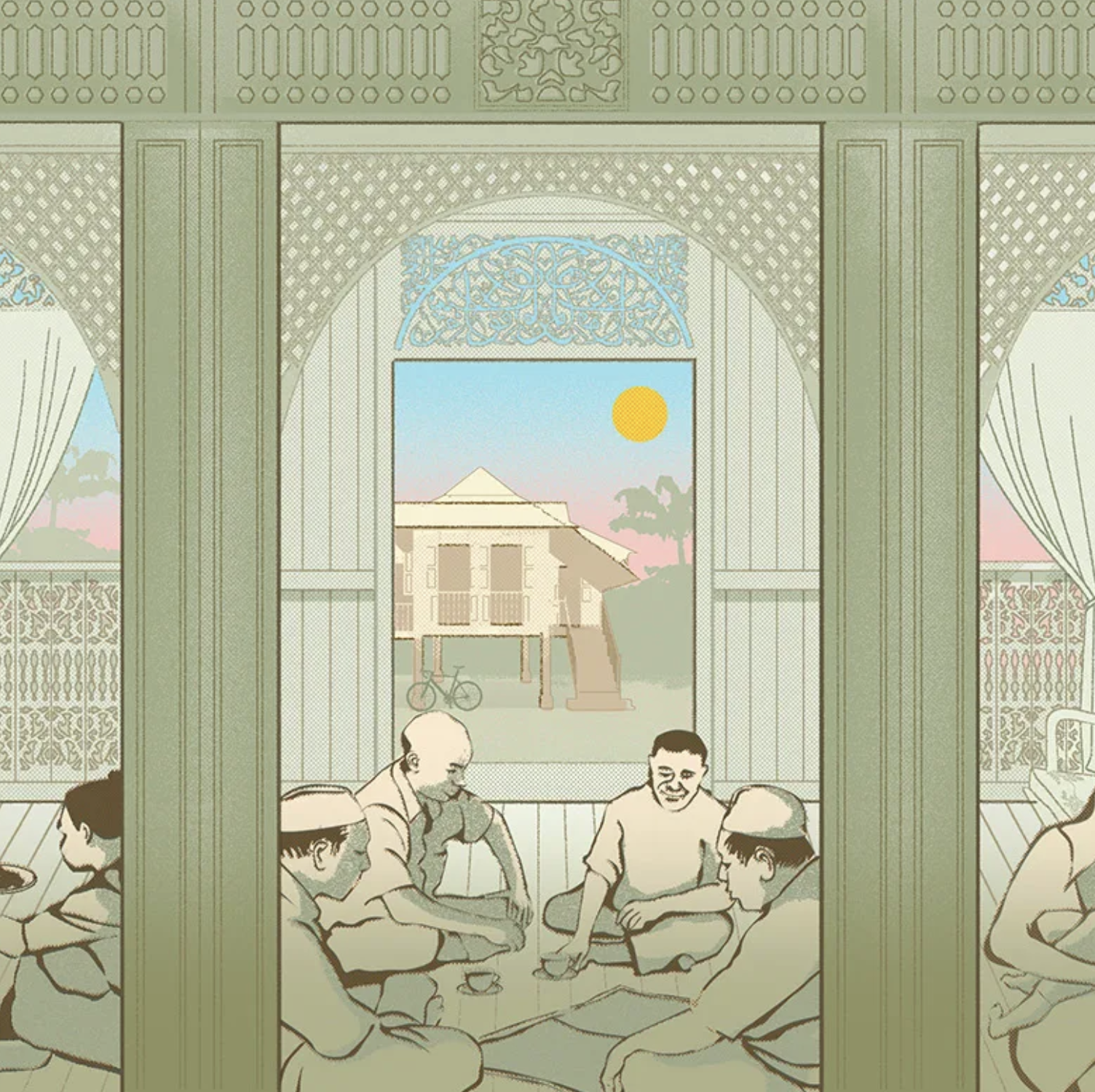

How do local landscapes shape how people build their homes, and what kind of traditions do they hold dear?

Kawan special

How is cooking a symbol of community, memory, and cultural expression? In this article, writer Taahira Ayoob and designer Griselda Gabriele walk us through their process of putting together our latest piece on natural utensils in Tamil kitchens. This story is based on Taahira’s research trip to Sri Lanka, where she spent time with local women keeping tradition alive.

Stuff we love

↗ Bajawan weaver Katharina Paba from Central Flores was moved to restore her community’s ancestral cloth, the sacred Lawo Butu when her ancestors appeared in her dreams.

↗ Read through crowdsourced and community contributions of collectibles and heirloom memories from the Indian subcontinent in the Museum of Material Memory.

↗ A Nepalese youth calligraphy foundation, Callijatra, is reviving once banned Indigenous Nepalese scripts found on many stupas and ancient artefacts.

↗ Follow Jane Zhang as she uses everyday data to preserve cherished family recipes beyond the typical cookbook format.

Did you know?

The poetic versatility of the word “sayang”

The poetic versatility of the word “sayang”

The word “sayang” can mean the act of love, a term of endearment, or an expression of longing in Bahasa Indonesia and the Malay language. However in these languages and others like Tagalog, the word can also refer to an expression of regret and misopportunity. Its meaning captures the poetic connection between love and regret over what is lost, or missed. The song below captures this complexity—the word “sayang” referring to the singer’s beloved, his regret that they cannot meet in this world, and a promise that they will reunite in the hereafter.

Namun ku takkan putus asa

Duhai kasih pujaan kekanda

Di dunia kita tak berjumpa, sayang

Ku menanti di ambang syurga

Translation:

But I will not despair

Oh my dear beloved

In this world, we won't meet, sayang

I will wait for you at the gates of heaven

— Menanti Di Ambang Syurga by Ahmad Jais