My grandma does decolonial work — issue #60

What can we build with our real and righteous rage?

— Pooja Nansi, The Feelings of Brown People: A Radio Dedication Show with a Forever Engaged Hotline

In our October issue, Peiying wrote about how we formed a reading club around coloniality, knowledge, and being. In these sessions, we discussed the ways colonial and imperialist thinking continue to shape our behaviour and perception of the world, and read texts from amazing decolonial thinkers such as Frantz Fanon, Gayatri Spivak, Eve Tuck, bell hooks, and Robin Wall Kimmerer. These rewired our brains a little bit, but also reaffirmed things we’ve long thought about but have not found the right words for.

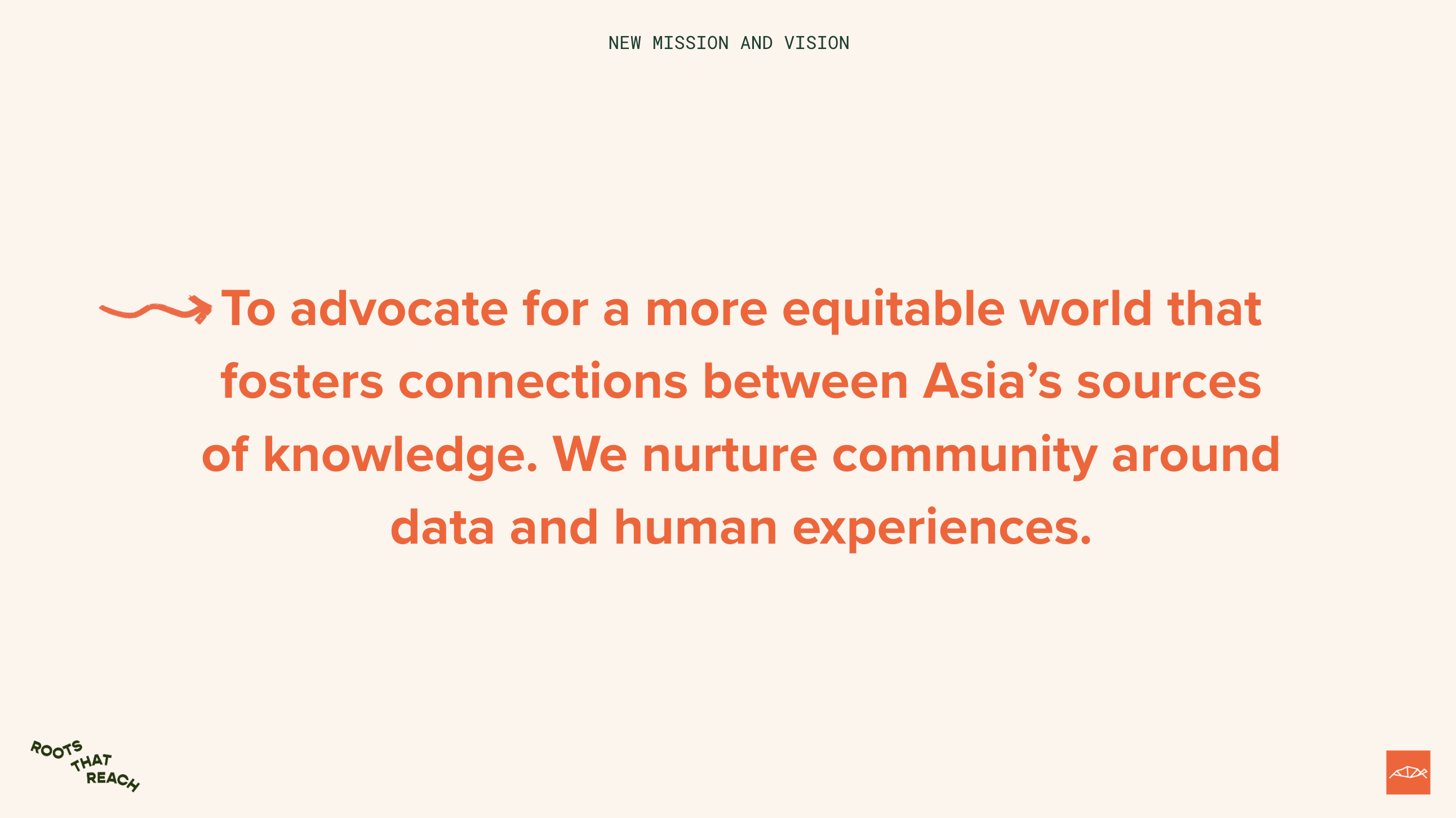

We’ve always sought to tell stories that showcase the diversity of Asia as a counter to western narratives, and thought of our practice as a decolonial one. But these days we’re contending with how data itself is a form of eurocentric knowledge, and how data visualisation as a practice can be reductive. As we’re clarifying what is important to us, we realised that our old mission and vision was becoming out of sync with our values. What systems had we inadvertently been supporting?

Data can perpetuate stereotypes and be used to suppress. But data can also be empowering. We have created work in which data were crowdsourced, and brought communities together. This year, we also want to show our readers how interventions with data can bring repair and healing. There is still so much we can do with data that can help us create the world we want to live in, and hold tightly to what makes us human. So, our team dreamed up a new mission and vision:

We’ll be putting this into practice in all strands of our work, including our stories, events, and of course, this newsletter. If you’re a regular reader of notes from the equator, you might not be surprised by this development. This has always been the space for us to speak more directly to you, where we tried to find words for what we’re thinking and feeling, and share our uncertainties and difficulties, especially when the world barely made sense. We’ll continue to interrogate the power of data and the responsibility we hold as data journalists.

This year, we’ll be practising this new vision with you as part of a decolonial data storytelling practice. We’ll be paying attention to diverse sources of knowledge–not just data, but also ancestral knowledge, memories, and local stories, and finding ways to explore this in our work. But we acknowledge that what we’re doing is not really new. In one of our discussions around decolonial theory, a teammate commented: “My grandma knows this. And she doesn’t use big words”. We all murmured our understanding.

Perhaps all we’re doing is going back to the heart of what is familiar. Our roots.

more from us...

Our first story on Singapore’s public housing asked: Does the system really serve everyone?

What would we be without trees? A lot hotter, shows our analysis of green space in Asian cities.

Kawan special

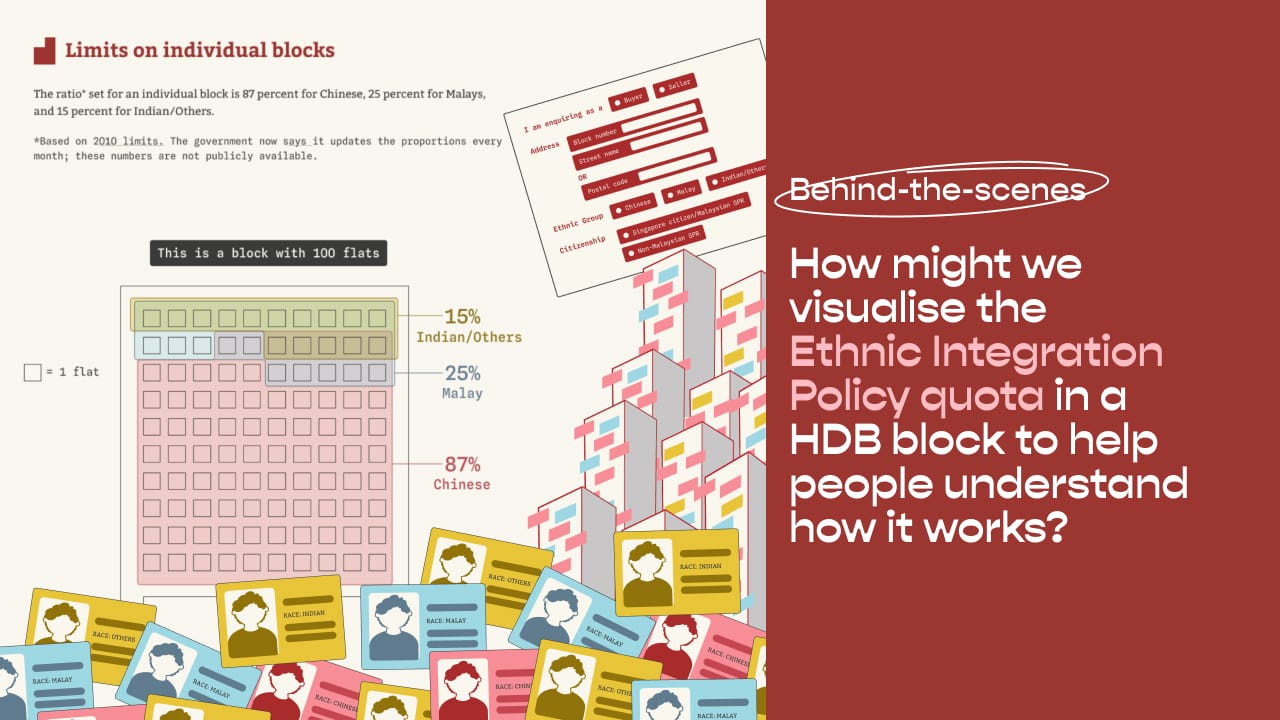

Singapore’s Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP) allocates quotas in public housing blocks based on ethnicity. In our most recent piece, we examined the EIP and its impact on homeowners, particularly those from minority ethnic groups. In this behind-the-scenes article written by Siti Aishah, our Frontend Web Developer, she provides a closer look at the ideas, prototypes, and key decisions that guided the development of one of the key visuals in the story.

Stuff we love

↗ On the fringes of one of the Philippines’ most urbanised cities, a mangrove forest is unexpectedly thriving.

↗ Amid environmental degradation in India’s Arkavathi river basin, a community taps on nature-based solutions to revive its wetlands.

↗ Don’t let the headlines get you down; this tree map of positive news from 2024 is worth celebrating.

↗ What predictions await you on the Year of the Snake? Find out here.

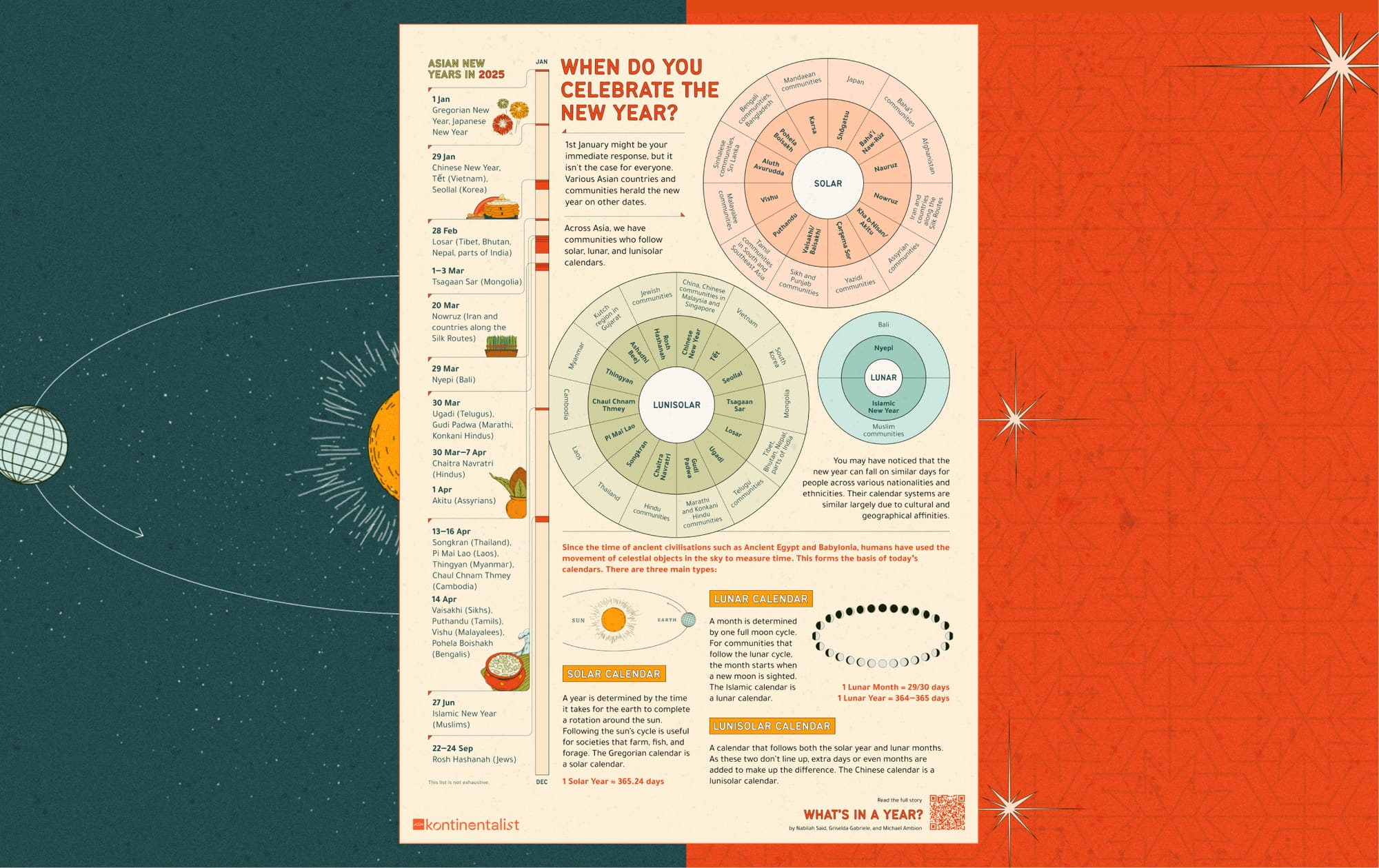

Did you know?

Fire warfare on the eve of Nyepi

Fire warfare on the eve of Nyepi

On the eve of Nyepi, or the Saka New Year, Balinese Hindus carry out a tradition called meamuk-amukan. Originating from Padang Bulia village, the practice involves a fire battle between men using danyuh, or dried coconut leaves. The burning leaves symbolise the anger that can flare up within humans, before dissipating. The tradition teaches people to control their anger and not hold grudges, much like the fire of the danyuh which quickly burns out. Meamuk-amukan has no concept of victory or defeat, instead reinforcing the value of togetherness and brotherhood.