Meet the Community! Keng, Data Editor at Pulitzer Center and Data Journalism trainer/consultant

Kuek Ser Kuang Keng studied chemical engineering as an undergraduate and worked as a journalist for Malaysiakini for 8 years before going…

Meet the Community! Kuang Keng, Data Editor at Pulitzer Center and Data Journalism trainer/consultant at DataN

Kuek Ser Kuang Keng studied chemical engineering as an undergraduate and worked as a journalist for Malaysiakini for 8 years before going to NYU Studio20 on a Fulbright scholarship and working as a Tow-Knight Entrepreneurial Journalism Fellow at CUNY. Besides data journalism, he also supports open data ecosystems by bridging the gaps among different stakeholders and within government agencies. He’s now Data Editor at the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting, a Data Journalism trainer and consultant at DataN, and also runs the annual Sigma Awards which recognises the best of data journalism.

You’re one of the most recognisable names in the Asian data journalism scene. You play several roles — data journalist, trainer, as well as information literacy and open data advocate. How did you first get drawn into the fields of data visualisation and journalism?

I think it has something to do with my first degree being in chemical engineering. When I was at Malaysiakini, whenever there was any data crunching needed in the newsroom, they would pass the project to me.

Later, when I got the Fulbright scholarship to study in the US at New York University, it exposed me to how data journalism was practised in big American newsrooms. That was when I realised how powerful data journalism could be, and that it could be something that I might excel in. After I finished my Master’s, I applied for a Google fellowship, which sent me to a few newsrooms to help them start their data reporting efforts, including Public Radio International and International Business Times.

Then I went back to Malaysia in 2015 — at this time, data journalism was very new in the region. But I didn’t go back to Malaysiakini as I was, by then, more of an editor doing more leadership and coordination stuff than reporting, and I felt I’d be doing the same thing again and not doing justice to what I’d learned if I rejoined the company.

I felt very strongly about wanting to learn more about data journalism — those two years in the US weren’t enough. Since there was also a knowledge gap in the region, I formed my own company, Data-N, to help newsrooms build their capacity in data journalism. I had joined the Tow-Knight Entrepreneurial Journalism fellowship in my last four months in the US, which was similar to an incubator program where we learnt how to build up a business idea we had. Using what I had learnt, I built a training module and business model, and asked myself questions like, “What newsrooms should I approach and what would they need?” and “What kind of network can I use to reach them?”

What is special about data journalism for you? In a previous interview, you said it had 3 things that made it very suitable for the digital era: critical thinking, data literacy, and digital capacity. Is it also about — like what Eva Constantaras said — an attitude of daring to make original conclusions from the data, rather than deriving the reporting from secondary literature?

Data journalism is actually about using a very scientifically sound research method to look at an issue — we’re kind of like social scientists, although we’re not trained as such.

Very early on, I was told by two New York Times journalists that data journalism isn’t about the data or visualisations — it’s about how you analyse something with critical thinking. At the core of it, strong journalism is about critical thinking.

Traditionally, we like to rely on experts to tell us what is good or bad practice. Data journalism gives us an opportunity to practise our own analytical skills when we approach an issue. It also encourages alternative methods of analysis — for instance, instead of using data provided by the government, we can look at crowd-sourced data.

Digging into the data journalism pieces you’ve produced — are there certain topics or approaches you prefer and why? It seemed like you emphasised on making a topic relatable for the audience.

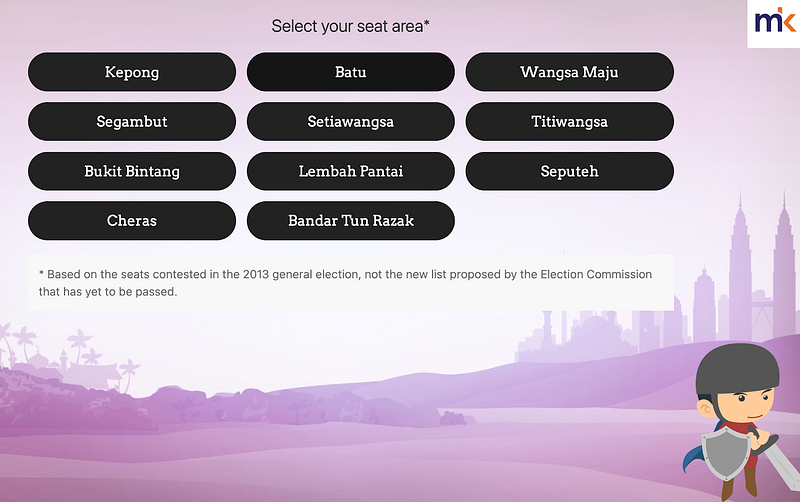

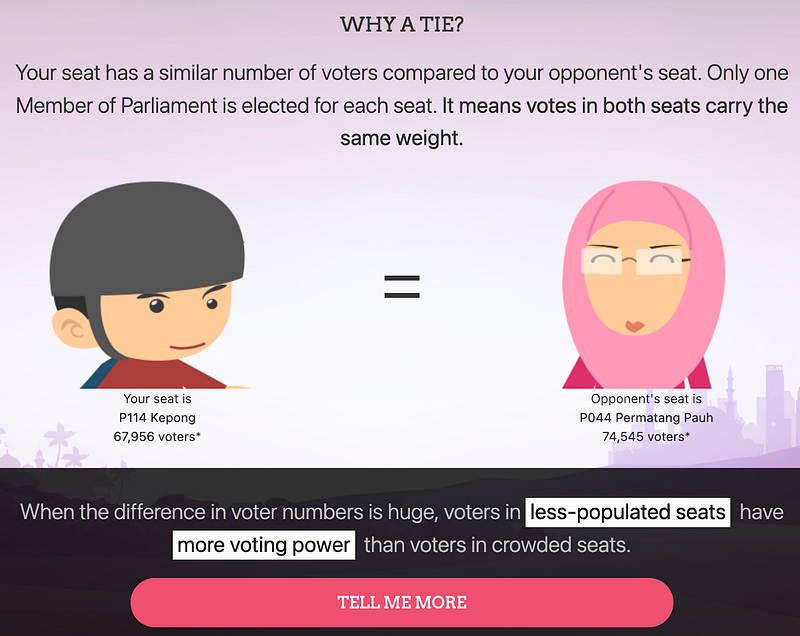

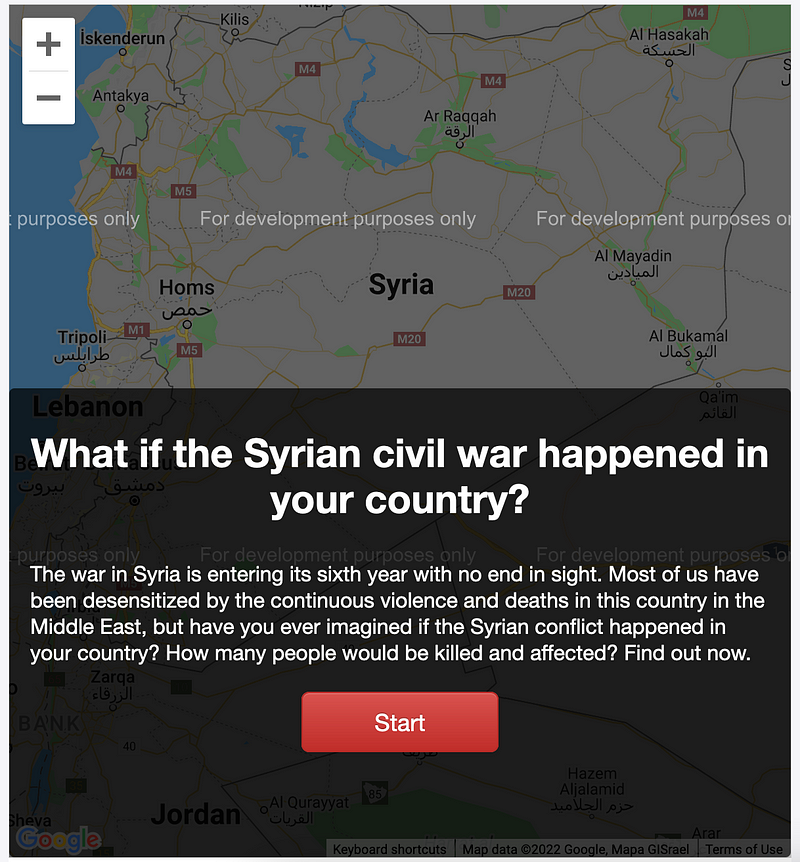

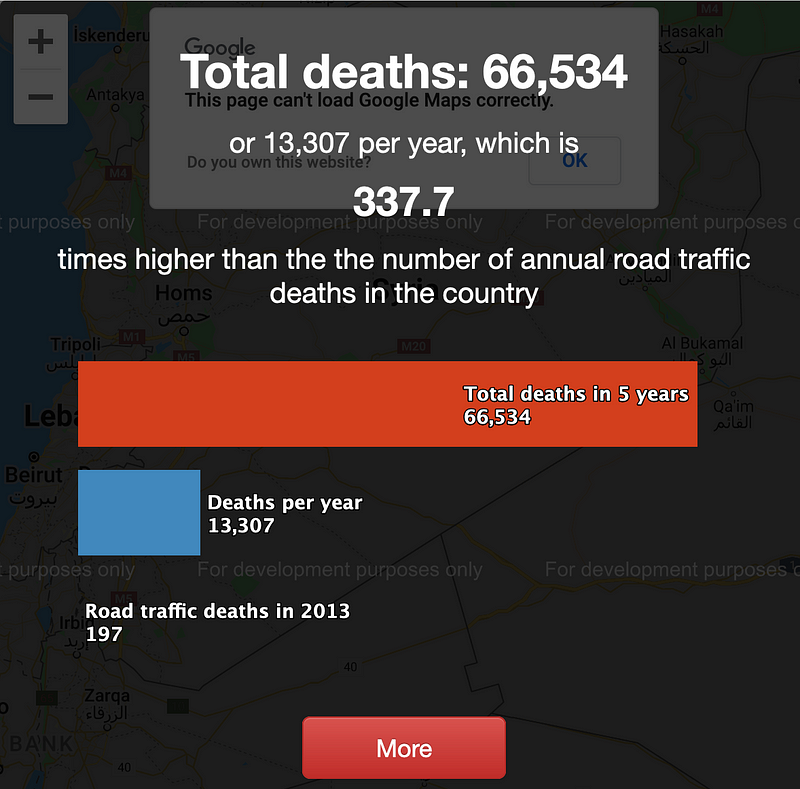

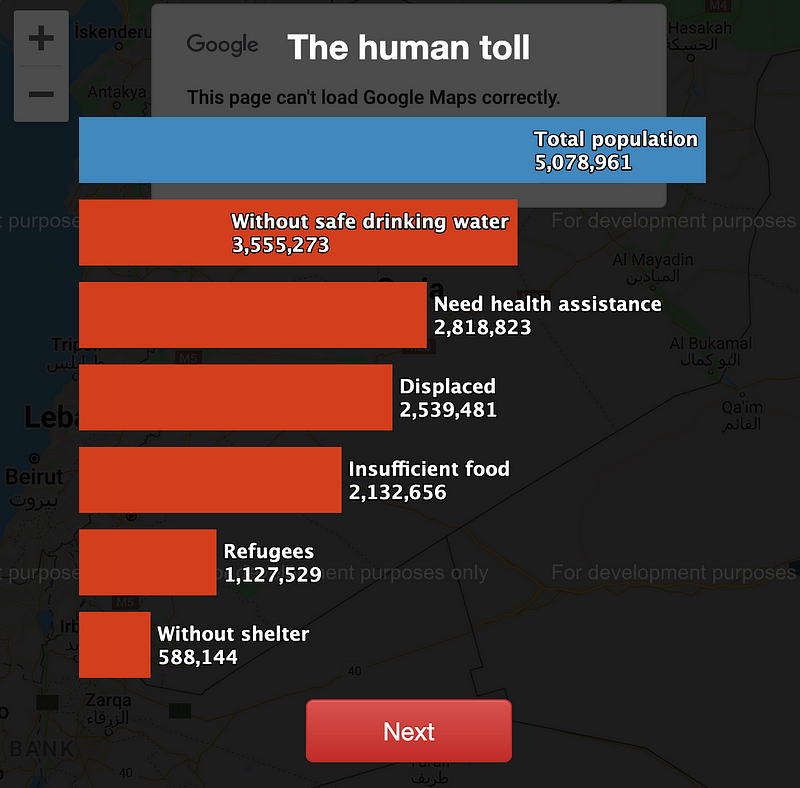

It is not about what I like — it’s more about what I could do at different stages of improving my skill. When I first started, I was not very good at doing very technical big data analyses, so I spent time crafting my presentation skills. At PRI — which was where I did the Syrian Civil War piece — I didn’t have a huge team to do fancy visualisations, so we tried to be more creative and did simple data analyses. When I came back to Malaysia, I was able to do more front-end development work, so I could create that election news game.

The latest story I did was about the Hong Kong pro-democracy protests, and it asks how misinformation that originated from China and Hong Kong reaches Malaysia. Here, I was more confident with my skills involving larger datasets. So the projects reflect my own learning process.

How would you describe your experiences as the Sigma Awards founder/judge and as Pulitzer Center’s Data Editor? What have you observed and learned?

Sigma Awards is really very exciting — each year, we receive 500 to 600 entries from all over the world. Through this competition, you find out about applicants you’d never heard of before and you get a lot of inspiration from them. This fits perfectly with my training and consultancy, because I’m updated about what’s happening on the ground.

Pulitzer Center is totally different. After some years of doing training and consultancy, I realised that I didn’t really have the time or platform to train myself, and if I can’t do that, then my consultancy would also stagnate. As Pulitzer’s Data Editor, I play a role in data support — I’m somewhat like a technician for journalists. For example, someone once requested for help to create a database by scrapping Peruvian government websites. I said sure — I didn’t actually know how to do that (laughs), but then I figured it out.

As for trends that I observed: cross-border collaboration is becoming more systematic and structured. If you look at the Pandora Papers, they basically built an online database where everybody can access confidential personal and corporate information securely, and use the information in collaborations.

There’s also more sophisticated technology being done at the forefront of data journalism, like machine learning, to work with big data and to automate a lot of investigations. The Pulitzer Center works with specialised groups such as Earthrise Media, which applies machine learning and AI capabilities to analyse large amounts of satellite images. [Added post-interview: Early this month we (Pulitzer Center and Earthrise Media) have launched Amazon Mining Watch (https://amazonminingwatch.org/en), an open data platform where we share the geospatial data of mining activities in the Amazon detected by using machine learning to scan satellite images.]

What’s the motivation behind your personal focus on teaching and training people?

The ultimate purpose of journalism is to have an impact and to make the world better. You can’t do that alone in one newsroom. You have to do that collectively. If you’re a good journalist and you’re helping a newsroom produce some award-winning stories, that’s good. But in terms of impact, what if you’re able to contribute to more newsrooms and build their capacities, so even more newsrooms can produce impactful stories?

I was given the privilege to further my studies and expose myself to some of the latest technologies in journalism. So when I came back, I wanted to use that privilege to fill the knowledge gap in data journalism for the region, and more importantly, to do so specifically for small and medium newsrooms. All my life, I’ve been trying to build better journalism skills, not only for my organisation but for other newsrooms as well, because journalism is a collective thing. You can’t just encourage one or two newsrooms to grow, you need to do so for the whole industry and ecosystem.

How do you persuade them that this is achievable and a priority for their resources?

When I first started, I actually did a lot of training outside of the Southeast Asia region — India, Nepal, Taiwan — these places were early adopters of data journalism. I first approached them and used some of my network in the US — such as the BBC, who wanted to train journalists in the region. That helped me build my business. Simultaneously, I did a lot of free advocacy work. I kept talking about data journalism in conferences, where I met with editors. Actually, it’s relatively easy to convince people to get into data journalism because of its fancy presentation — you can easily get the attention of editors and journalists and they’ll say, “Oh, wow, this is great. I want to do this as well!”

Once Malaysiakini started to do a lot of data journalism projects, the other newsrooms in Malaysia wanted to do them as well. So what you really need is someone to first start it and do it well. And it has to be good, because then it’ll attract the attention of the competitors. I think that’s how, in the last two or three years, data journalism has gradually been established in this region.

When social media first came, data journalists in the region were all crazy about it and wanted to do everything on it. After some time, they realised that if you depend too much on social media, it’s tough to adapt whenever the algorithm changes. So I think there has been a shift from chasing for eyeballs on social media back to achieving journalism quality. The rise of subscription models also means that you’ll need to produce unique, exclusive content, so that people would be willing to pay for your content — so I think that is another factor that pushes people towards investigative and data journalism.

How did you develop your business model in Asia, and what’s the market landscape now in terms of the diversity and the maturity of newsrooms across Asia?

I didn’t put all the eggs in the same basket when I started. I still did reporting and projects for PRI after I returned to Malaysia. Over time,I realised that approaching newsrooms one by one was not very efficient. Instead, I decided to work with journalism organisations to provide training to their member newsrooms. So I became the training partner for WAN-IFRA in Asia, Google News initiative, and Facebook.

In Asia, there are more people coming into the market, such as new startups in this region such as Kontinentalist. The old newsrooms weren’t able to innovate as quickly. These newcomers pick a niche point and do it really well. Like Kontinentalist does maps very well, and Indonesia’s Katadata does data (specifically compiling and cleaning data from government sources) very well — I trained them two years ago and now they have a huge team. The big newsrooms do realise this and try to incorporate these innovations, but because of their structure and the ‘old guards’, they face a lot of hurdles.

I’m quite optimistic about the industry in this region because we no longer have this monopoly by huge traditional legacy media. Digital platforms keep coming up — you used to only have Facebook and Twitter, and now you have TikTok. Recently I found out about Xiaohong Shu, which is also very popular among the Chinese-speaking communities here.

There are still some problems with media freedom restrictions in certain countries, and because of that, independent media find it really hard to survive even if they have great technological capacity. Singapore is special because, while it doesn’t have a lot of media freedom, it is a regional hub and able to attract a lot of talent. And when you are doing your coverage, as long as you aren’t too critical of the Singaporean government, you are still able to do a lot of things.

Do you think we’ll see legacy players disappear as they’re supplanted, or is there space in the market for them and newcomers to co-exist, e.g. start-ups supplying parcels, stories, or data production?

People’s behaviour with regards to information consumption has changed a lot — we use multiple platforms to get information, and it’s not realistic to ask any media company to cover all the different platforms. Now, there are actually many small markets that each player can try to capture. If you are very good at TikTok and in storytelling, you can accumulate followers there.

The legacy media will have to downscale. Their market is not as big as it was in the past. They can create spin-offs within the company — perhaps a unit that focuses on one platform — but I don’t see the possibility of one huge team conquering all the different markets.

When legacy organisations want to innovate, they can work with specialised service providers — like Kontinentalist, who can produce interactive stuff for them. But I think big newsrooms will eventually realise that they have to have their own team, if they have the resources.

But it’s very hard to say — who knows what will happen in the next few years? It also depends on the tech companies — will Facebook be broken into multiple companies? As everybody is rushing into this metaverse thing, how would that push tech companies to evolve?

You’ve spoken about being optimistic about Southeast Asia’s media or journalism landscape, partly because, in the West, it’s a saturated market with lots of legacy media, whereas over here, there are millions of users who are jumping straight to mobile. But how do you weigh up this potential positive of being in Southeast Asia against other less positive factors, such as some countries not having the same resources or culture of financing journalism in this developmental stage?

Developing countries don’t have an ageing population, so young people are coming up, which means there are always new markets for you to capture and there are more young talents who are able to come up with new ideas.

Factors like media freedom — there are ups and downs. Take Myanmar for example, there was hope five years ago when Aung San Suu Kyi and her party were included in the government. There was huge investment going into the country, including into media organisations. It boomed, but then things sort of collapsed. In 2018, Malaysia had a change of government, and there was a lot of hope for more media freedom. And then the so-called ‘coup’ happened two years ago. So journalists in this region are used to it — if you’re able to survive when things are bad, then when things become better, you’ll be able to grow. I think that’s what makes the journalists here more versatile and flexible. There are a lot of good journalists here with very strong dedication, like Maria Ressa in the Philippines.

Malaysiakini has 25 years of history. When I first joined, media freedom was really bad. Our company was raided, computers taken away, and our editors went into hiding. Compared to then, we’re now considered mainstream and it’s better. We can find a lot of these examples in this region — those who have struggled against authoritative governments and oppressive environments to become success stories. Like Indonesia — in Suharto’s time you could get killed. Journalists in the Philippines do still get killed. But there’s progress in other countries. So I don’t think this is something that we should feel pessimistic about — there have always been ups and downs.

You urged young journalists in a GIJN interview to return to the region. What would your pitch to them be?

Journalists are not people who are looking for a comfortable life. We’re always looking for adrenaline pumping moments and excitement. If you want to have greater impact, come back here where there are a lot of gaps that you can fill. Also, we have lots of new audiences, ideas, and young people emerging. If English is not your first language, then use your native language — work in your own country so you’ll be able to express yourself better. So, get some experience, learn some new skills, then come back here where there are a lot of opportunities, especially at this time.

You’ve also been an advocate for open data. How much do you feel like that promise of open data can be realised in a regional context?

The governments realised the more data you open up, the more commercial value you’re able to create. So it’s for economic purposes, not because they think transparency is important. They balance between wanting to open up and to protect their power. Governments aren’t going to roll back their open data policy — it doesn’t make economic sense. It falls on us to use the data available in our reporting.

China has one of the most authoritative governments in the region, but they’re actually quite good in terms of releasing open corporate data. The Shanghai stock market allows you to find filings by companies. For example, Reuters did a story about the Henan government by looking at their tender documents — one of the tenders was about building a civilian system to monitor foreigners and involved installing CCTVs, face recognition technologies etc. Similarly, one of our Tempo fellows at Pulitzer Center did a story on deforestation in Indonesia by looking at concessionaires given to logging companies.The Malaysian government knows they can’t miss the train. What’s stopping them isn’t that they want to keep secrets, it’s that their technical capacity to build that data infrastructure isn’t strong enough yet.

Do you see a gap between what’s being produced and what’s actually appreciated by the public?

It is a two-way thing. If you just keep saying, “They don’t read charts so we won’t produce any charts”, then you won’t be able to educate your audience. After the pandemic, a huge part of our society has become very numbers-sensitive. They now know what is R naught.

Actually, the best data journalism skill is to tell data without telling it. I think that’s the highest form of this craft — you use data to inform your reporting, but your reporting is not data heavy. Your reporting is still about telling stories and interviewing people, but behind the scenes, it’s the data that guided how you came up with the story angles and conclusion.

One of our fellows at Pulitzer Centre published a story about the leather supply chain from Brazil to the US. She was able to trace that the leather was coming from illegal ranches in Brazil. In the whole story, there wasn’t even one chart or heavy data analysis involved (laughs). But that story has great photos, great videos, and great interviews. How did she find those people to interview? Through data.

Remember, nobody can cover all the bases, so different organisations should have different strategies. If you’re writing for the business community, you can go data heavy — it should be okay. If you’re writing for school kids, then you have to take a different approach.

Do you think sustainable independent journalism is possible with subscription models?

Subscription is the way to go in this region. If we really want to have our own independent media, we have to build our own community. Two very good examples in this region are Malaysiakini and Rappler. Malaysiakini was sued by the government for hundreds of thousands of ringgit, so they had a crowdsourcing campaign to pay the fee and hit the target within less than 12 hours. So people are willing to pay if you are able to prove that you have the values. For this region, where we’re in more oppressive environments with very strong governments, we can’t rely on advertisements as that’s very politically sensitive. When the companies paying for advertisements see the political environment is different, they will change very fast.

Philanthropic funding is also not sustainable. If your government disagrees with you, they can cut that funding very easily. Singapore recently passed a law that stops organisations from getting foreign funding, for example. We have the same law in Indonesia and the Philippines.

Is there work in Asia that you really like?

In China, there are very good data journalists even though they operate in a very restrictive environment. For example, Pengpai is very good at journalism/activism. Taiwan produces some of the best data journalism work in this region as well — READr is very good. Hong Kong is really struggling currently, but there’s Stand News (立場新聞). Myanmar Frontier also produced some very good investigative pieces, but they’re currently in trouble. Kyrgyzstan Kloop is also very good. Take a look at the winners and the shortlist entries from Sigma Awards, especially those you see from small newsrooms. Asia actually sent in the largest number of entries!

Do you have advice for our readers?

When you first look at data visualisation, of course, you are attracted by the visuals. But if you’re really aiming for impact — to make a change in our society, to change laws and policies — data and visualisations are actually just tools. Ultimately, it’s about the story, and presentation is secondary — what kind of information have you delivered? That’s something I’d like those who do data journalism to always remember, because that is how we build our values.

Any specific tools and resources you recommend?

- Edward Tufte’s books are good.

- There are some newsletters that you can subscribe to, including: Off the Charts by the Economist, Top 10 in Data Journalism by GIJN, Conversations with Data, Newsletter by J++

- There’s also the data journalism handbook from DataJournalism.com — some of the best data journalists gathered to write this book together, which is quite impressive.