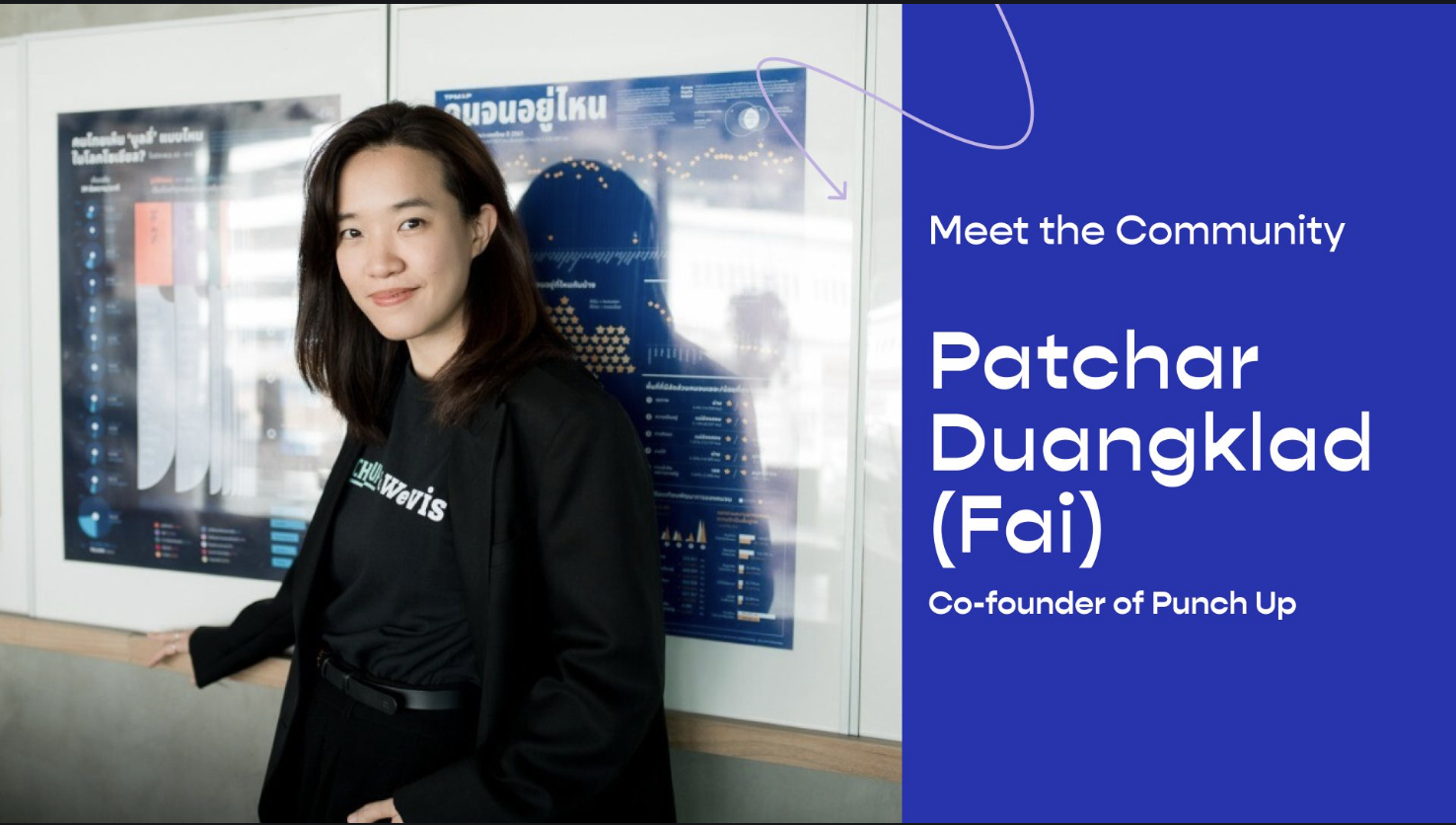

Meet the Community: Patchar Duangklad (Fai)

Patchar Duangklad (Fai) is the co-founder and business developer at Punch Up, a Bangkok-based data storytelling studio that creates meaningful conversations with data, design, and stories. Coming from a background in public policy and media, Fai shares her journey in setting up Punch Up, as well as WeVis, a civic technology organisation, her passion for political participation through data, and her vision for the evolving data landscape in Thailand.

How did you find your way into data storytelling?

I did my Master's Degree in Public Policy and worked with a policy think tank for a couple of years. Then I [shifted to] the media field, and made a documentary about social [and] public policy issues, [which was broadcasted on TV]. It's very interesting to bridge the world of academics or policies with the audience.

I [eventually] moved to another media content agency, and that was the starting point of Punch Up. I met my business partner, GG (Thanisara Ruangdej), who was an editor and journalist at that agency. Back then, in 2019, we had a general election [for the first time] in eight years after a coup. [This was a new experience], especially for young people. There are so many examples in the United States where they have data-driven content about election candidates, and it's a very useful way to communicate with the younger generation.

There was a project called ELECT [we did under WeVis], and our objective was to help the younger generation get involved in politics. To [make them aware] about their candidates, so that they feel more [connected] to the election and politics, because they hadn't participated in the political field for many years after the coup.

Right after we finished that project, my partner and I, as well as [three other partners] became the co-founders of Punch Up. The five of us [discussed], and we thought, [back when we were at WeVis], it was very impressive how people were interested in this kind of journalism, which was quite new to Thailand back then.

We were so excited! There's a lot of potential not only in the field of politics, but other areas like education, environment, and broader journalism as well. We like to call ourselves a studio because we don't want to be media, but it's also very hard work to be a media organisation, right? The business model is quite difficult. So I thought we could work hand-in-hand with other media outlets, and organisations that have information or data to communicate. So that's how we founded Punch Up. I see the value in communicating with data because it's very powerful. [Data] can [begin] conversations, where you have something objective to discuss and ask further questions [about], and [data can be] used in many ways.

Why do you think data-driven communication resonates so much with the younger generation in Thailand?

It's not [a] one-way communication. Data has the power to [make people] feel like they can ask questions by themselves. In our role [as communicators], we can facilitate the audience, to [enable them] to ask more [about] the data. They can participate more after they learn about this information.

One of my favourite things about Punch Up is the name of your studio! Can you share the story behind choosing it?

We wanted to name it “punchline”, but that name was already taken. We still liked the word “punch”, because it's very active. [To us,] punching is like transforming something offline into the digital—back then, there was this punch card that they used for coding. So [“punch” meant] transforming everything into a digital format, [in order for you to] learn about data. That's the first meaning.

The other meaning [is this]: Fighting power or making fun of the elites. We want to fight and encourage democracy. We visualise for democracy. We want to empower people with data by making data more accessible and interesting. It's not only about making data viral, but also about having some kind of tool or platform so that people can participate in political issues.

I'm sure you know this, but data is so tricky to obtain in Southeast Asia, right? Especially accessing open data. What are some data-related challenges you face in Thailand?

It's very difficult. Firstly, at Punch Up, we work as a studio [and] we have clients and partners. We have helping hands. We work with a government organisation focusing on education issues, [and they help us] get access to data. We have help from partners, but we also have to find data in different ways. Even though we have some connections to get open data, it is still not an answer to all of our questions, or [the data] might not fit if they are very poorly formatted. So we have to be creative about data. One of our strategies is to acquire the data by ourselves. For [example], data from social media [can be scrapped].

We have our storytelling work, but we also work in policy advocacy. Let [the public] see, [what would happen] if [they] have open data, and what they can do about it afterward. We try to push this open data agenda as a civil society. There's still a long way to go. And then, [hopefully,] the government or those who have the data would think okay, it's quite important [to share the information they have]. The thing is that it's not that [people] don't want open data, but they don't know how or why they should [share it].

It's all about transparency, right? Once you give people information, you're essentially empowering them to form their own informed opinions and thoughts about what's going on. Sometimes, in our countries, there's this wall between the state and the people. It’s important to ask, how do you break that wall? How do you punch through?

Yeah, which is quite difficult, but you have to keep on punching. [laughs]

I also wanted to ask, how do you select your clients and partners?

For Punch Up, we focus on social and public policy issues, [which means our work is] not only [about] data-driven communication, but also impact-driven communication. So it has to be data that can impact society in one way or another. We have two main client profiles. The first one is newsrooms, the media houses. The data journalism scene in Thailand is not well organised, and they don't have the capacity to do something with new tools or have the capacity to learn.

We work with newsrooms, [aiming to build] capacity for them, to [use data storytelling skills] in their own [work]. But it's quite difficult actually. We [often pitch] training programmes [and] knowledge transfer sessions, but they have limited resources. Still, we [continue to] work with the media, because we think that it's very important to [teach] these skills, knowledge, and tools [to] those who already work with data, and help them [work with] it better.

Another part is the clients, which are [usually] organisations [such as] governmental organisations,[and] NGOs. They have their own [message] and they already have data in their hands. [Usually,] they want to communicate that [message] to people, sometimes [for a] campaign or policy support. We think that we can add our value to that communication, [and] do it better.

I resonate with that so much. Every day, I want to work with so many organisations and do a lot of projects. But to build a thriving scene, you also have to prioritise and strategise. I'm curious, in Thailand, is the needle shifting for the data journalism scene?

Yeah it is, actually. One of our first clients was actually [an online] newsroom. When they rebranded themselves, they wanted to set up a data journalism department. So the demand [is there].

[However,] in many newsrooms, [while] they have the idea that data is important and useful in some issues, they don't see it as a permanent thing. They don't develop [data storytelling skills] for the long term. They use it as one type of format for [one specific] issue. For example, during the elections last March, many newsrooms were doing visualisations. But it was only during the election period. After that, they went back to [just] making graphs or tables [to complement the text]. They don't really like to use a data-driven approach, so it's a very ad hoc kind of theory right now. It's not permanent, and there's a demand, but it's not that concrete. I think maybe it's because it requires a lot of investment. So they can't afford that for now.

It's very different when data is at the heart of your story, versus when it's just an add-on. As you said, it takes a lot of effort and resources.

There are many opportunities and there's a demand for sure. Otherwise, we would not have existed for four years already. [laughs]

Being a co-founder comes with its own share of challenges and triumphs. What was a particularly rewarding moment for you on this journey?

For me, it's like building a house, an unfinished project. I feel like it's my work and my team. There's no one particular project format or outcome, but it's about creating this community. When people [read our work, and say], “I'm really interested in this, and I want to do this with my team when they have ideas”. And when [the audience] feel fulfilled by its impact. It's not [about a] big impact that changes everything, but [it’s fulfilling when] we gradually see [more] people use [data communication, and] how it can be useful in many fields. We cannot do everything by ourselves. We need friends or communities to help build this thing together.

What are your hopes and dreams for the field of data storytelling In Asia?

Starting from Thailand, I want to see data [become more accessible, to] help this kind of work. There's much interest and many demands. And we can see its impact. But it's very difficult [to create data-driven stories] because the infrastructure and the ecosystem are not that good, especially open data resources. Better infrastructure so that anyone who wants to do this can do it easier than us.

[Secondly, I want to] help develop data literacy for [our] audience as well. [For instance], if they see [data stories] more often, in more relatable ways, in many different forms, [such that] it becomes part of their life. [I want to tell them,] “Don't be afraid of data”.It's such a big dream. I don't know. One day, I want to make [data storytelling] easier for people and make it more relevant to them. It would be nice if we have that in the future. And when we reach that [vision], I think it's gonna be a lot of fun. [laughs]