Crafting Air Pasang Surut

Making meaning with Orang Laut Singapore for Hari Orang Pulau.

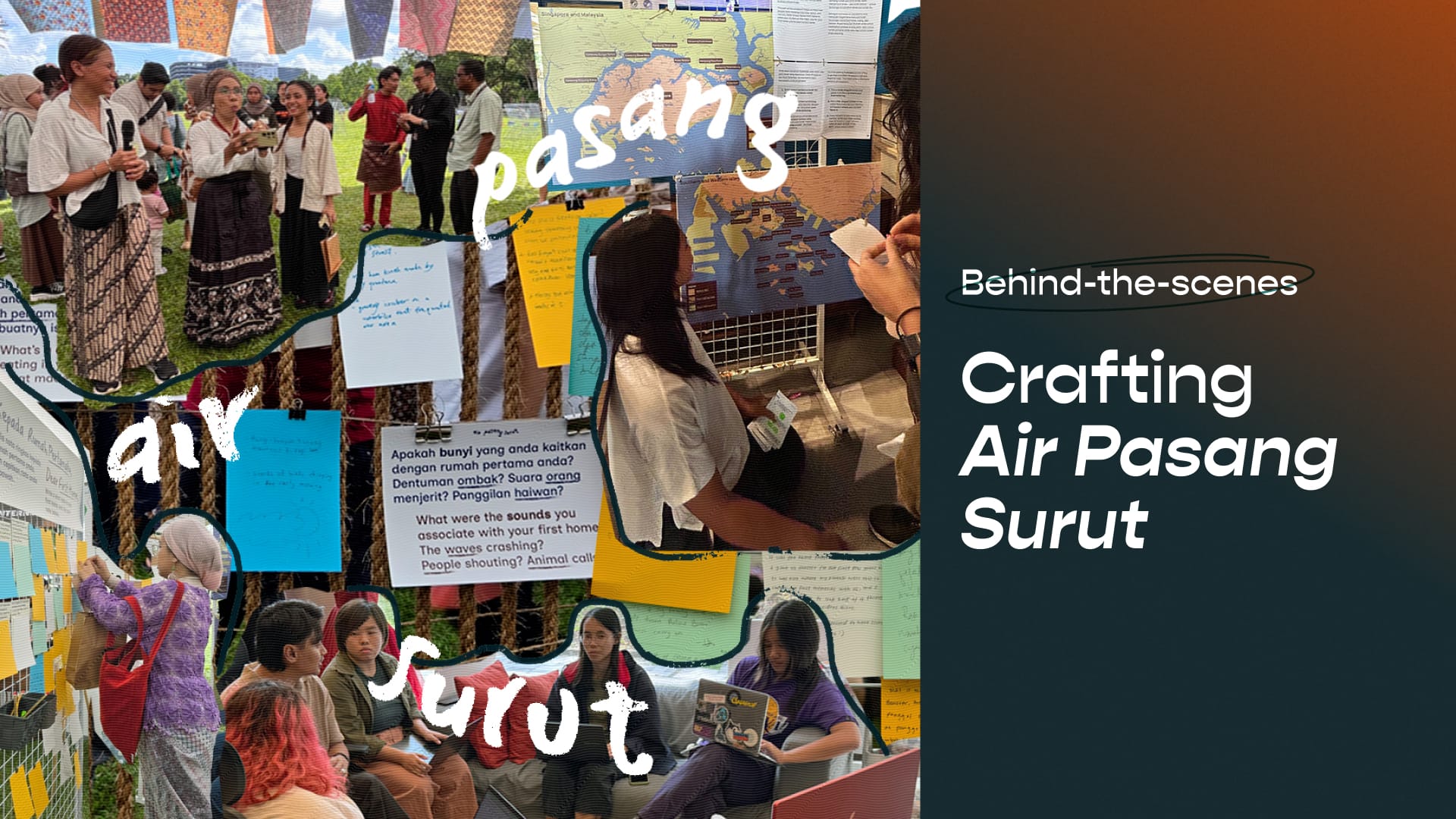

People learning joget dangkong, performances of silat gayong, lines queuing for bubur lambuk ikan tenggiri, jongs adorned with red, black and white sails, a bevy of colourful kain sarong fluttering in the wind by the sea; this beautiful tapestry of cultural pride and solidarity was on display during Hari Orang Pulau (a day celebrating the Indigenous islanders of Singapore), held at West Coast Park of Singapore on 14 June 2025.

Despite the sweltering Saturday heat, diverse crowds streamed in. Families from the Orang Laut and Orang Pulau communities laid out picnic mats and shared potluck food, while event-goers and curious passersby wandered between booths, talks and performances, engaging in conversations and learning with keen interest. Kontinentalist’s booth, Air Pasang Surut, meaning the rise and fall of tides, was set up at the edge of the tentage. Co-designed with Orang Laut Singapore (SG), the booth featured maps of Singapore, parts of Malaysia and Riau with the Indigenous names of each island and reflective prompts on home.

Left to right: Puan Asnida Daud, the host of Hari Orang Pulau introducing Air Pasang Surut booth; event participants participating in joget dangkong; crafted jongs (mini race sailboat) lined up at the entrance.

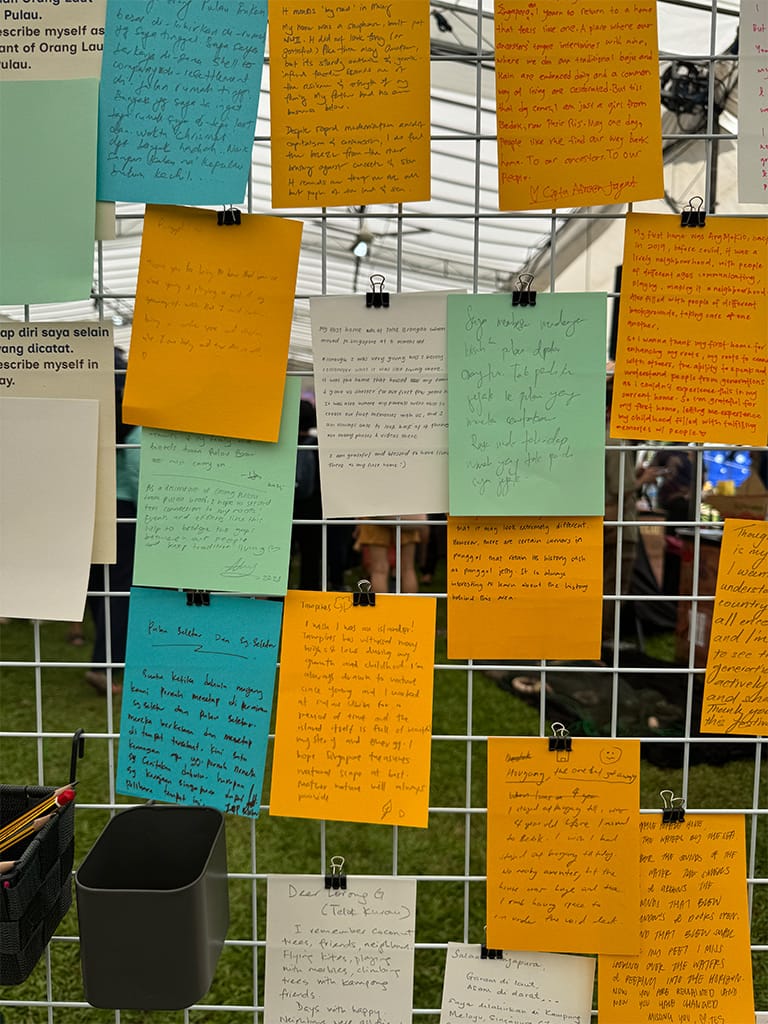

True to its name, our co-designed exhibit prompted responses and conversations that reflected an ebb and flow of complex emotions surrounding participants’ personal memories of home: longing, nostalgia, melancholy and more.

Diverse data lenses

At Kontinentalist, we’re widening our lens of what data and knowledge can look like. We acknowledge that lived, visceral experiences are powerful ways in which stories and knowledge are shared, passed down, and remembered. This framework has shaped our work with Orang Laut Singapore, a collaboration which began with Beyond the Mainland, a microstory on the realities of the Orang Laut’s displacement from Singapore’s Southern islands. The microstory looked at how the Indigenous sea-faring communities lived before being resettled to the mainland, and how their islands were repurposed or reclaimed in the name of Singapore's economic development. We also collaborated on Turning Tides, a walking experience led by Orang Laut Singapore at West Coast Park that traces the interconnectedness and lived realities of displaced communities across the region.

Their invitation to work together on a new project to research and gather recounts of the community’s displacement felt like a natural continuation of this work.

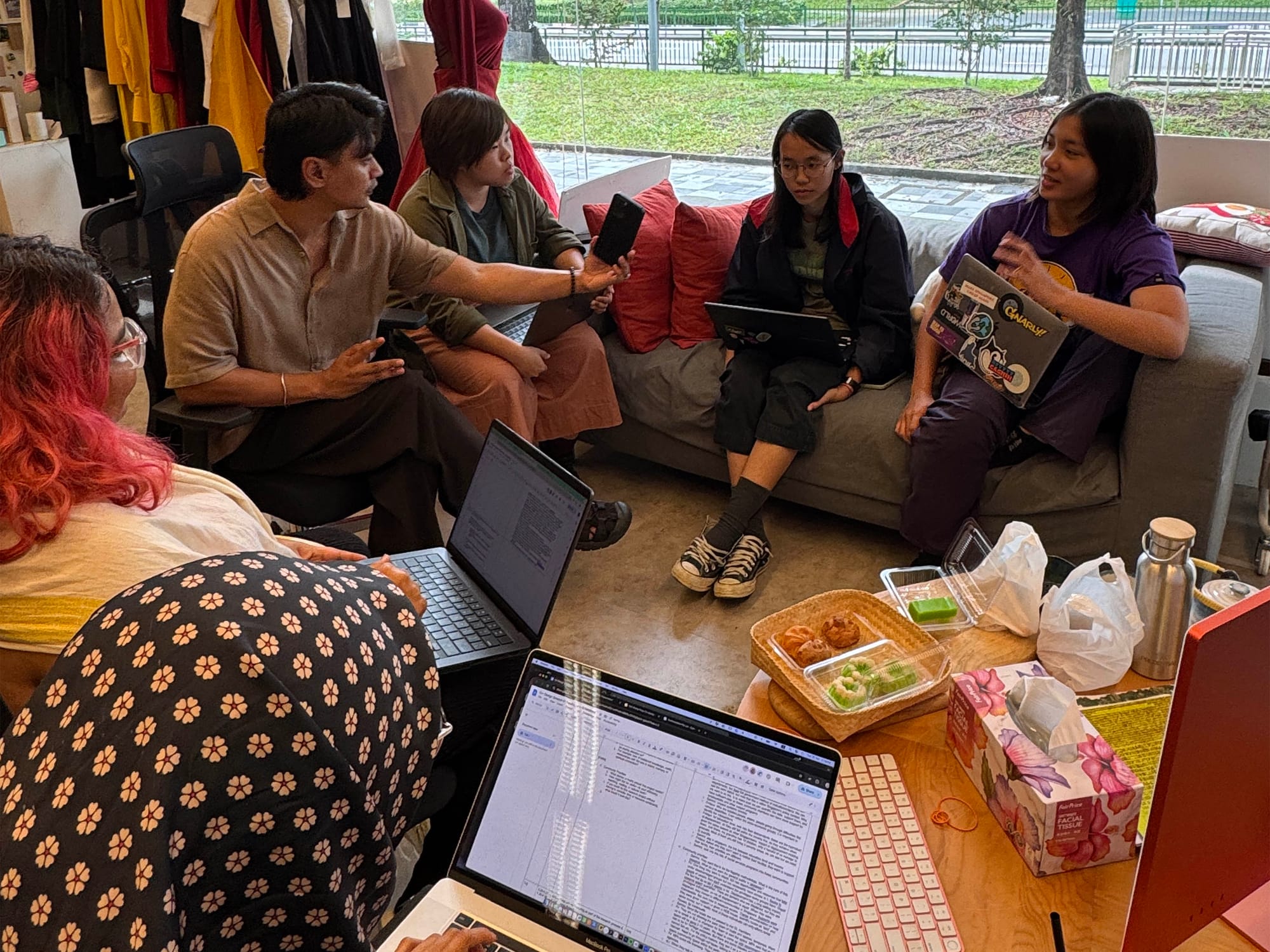

Air Pasang Surut couldn’t be realised without the many co-design sessions we had with Orang Laut SG. The process consisted of four two- to three-hour-long meeting sessions over a span of three months, where both teams collectively discussed the goals of the research and methods of engagement with the Orang Pulau and Orang Laut community during Hari Orang Pulau. These co-design sessions were key for us to craft a data gathering method which aligned with Indigenous values.

Learning from Indigenous models

“The double-edged sword of data shows just how important it is to understand how structures of power and privilege operate in the world.” — Data Feminism (2020).

Data agency and ownership demonstrates who has power, who doesn’t, and the power struggles that could emerge. To understand this, we don’t have to look far; many of the archived artefacts on Roots.sg, Singapore’s national digital archive, documents a tiny percentage of artefacts traced to Orang Laut. According to research in Lawan Lupa, most of these items are also labelled with vague and incomplete context, left as just “a thing” or “in need of interpretation”. This omission covertly reveals what the nation holds in collective memory of Singapore’s Indigenous communities.

Removing these artefacts from the daily lived experiences erases and essentially others the community which the artefacts belong to. Globally, the question of Indigenous data sovereignty is interconnected with many of today’s environmental, social, and economic issues. Indigenous communities have intimate knowledge and connection to their land and seas, but much of their agency has been eclipsed by settler colonialism and nation building.

Stories and memories are living artefacts belonging to their owners. We agreed that any data gathered from the exhibition would be owned by Orang Laut Singapore and their extended community. Existing and established frameworks of Indigenous data gathering guided us to work on this project with intentionality and care.

In shaping our approach, we drew inspiration from Indigenous frameworks that reimagine relationships to knowledge and the future. One was Te Korekoreka, a Māori future-making framework rooted in a historic 1849 karakia by Ngāi Tahu leaders, which facilitated future-making by honouring the past through a holistic worldview. Another was The Indigenous Stewardship of Salmon Watersheds project in British Columbia, which showed how non-Indigenous researchers could collaborate with Indigenous communities in ways that respect data sovereignty and protect environments central to their lives. These examples offered us not only guiding values for data stewardship, but also shaped how we carried out our co-design sessions and ultimately envisioned the method of exhibition.

One key takeaway from this research was that as external collaborators, we are removed from first-hand knowledge and connections from the Orang Pulau and Orang Laut. Hosting co-design sessions between both teams would ensure decisions are not made in a vacuum, and are instead created with transparency and alignment with the community’s values.

A seemingly small but meaningful act during these sessions was the serving of local delicacies (kuih) and tea, as well as space for flowing conversations, so everyone could feel welcome. For the exhibit itself, we applied similar principles: avoid leading conversations, and focus on organic, genuine engagement with participants.

As iterated by Firdaus from Orang Laut SG, attendees of Hari Orang Pulau were there to celebrate the joyous day. To position ourselves as data surveyors would have been intrusive, and potentially deviating from the festive mood. Our role was to build relationships and rapport with the participants. We learnt during the event that sometimes simply being present and listening attentively are more important than foraging data.

Weaving in clear objectives

While shaping the methodology for this project, we had to keep in mind that Orang Laut Singapore’s main goal was to unpack and understand the effects of displacement for the Orang Pulau and Orang Laut communities. To avoid casting a heavy mood around this topic, we reframed our inquiry around the movement of homes. Our approach was participatory, where everyone at the event regardless of their identity could reflect upon the idea of home and share personal experiences of relocation.

Home might mean different things to different people: it could mean land and environment, rituals and norms, or one’s cultural identity. While brainstorming, we pulled on different examples of participatory mapping, like the Waorani Mapping Process. Based on Indigenous community living in the headwaters of the Ecuadorian Amazon, everyone in their community is invited to contribute and draw their knowledge of the resources and features of their homes on large sheets of paper. The community then collectively decides which features are important to document.

These approaches inspired the outcomes of our ideation. Termed “Mapping Movements” the concept was to invite community members to highlight and reshape maps and boundaries, challenging official narratives by unveiling Indigenous stories and knowledge.

The two concepts derived from our ideation; Sharing Food Stories and Mapping Movements. Both concepts explore facilitating the sharing of stories.

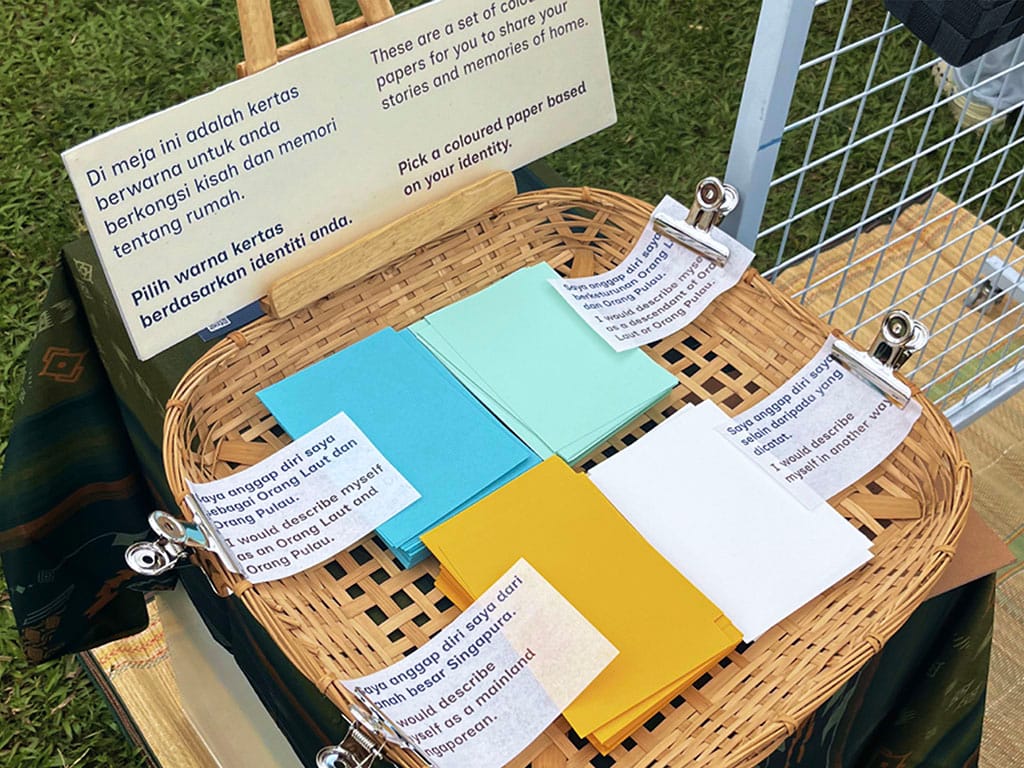

The concept was further refined and titled Air Pasang Surut. Centering the sea currents reflected how the concept of home has never been a fixed point for the Orang Laut. Their homes are not only shaped by their way of life, but also by displacement. The project’s goal evolved into identifying patterns and trends surrounding homes while creating space for shared reflection among islander communities, their descendants, and mainlanders. We opted for more reflective guiding prompts to avoid rigid categories and allow for open-ended responses. We considered language and access: many of the Orang Laut and Orang Pulau would be elderly Malay speakers and so the instructions were expressed in both English and Malay.

Translations were also carefully considered, since direct conversions often do not capture the intended nuance. For example, our phrase “Tracing Movements”, meant to reflect the shifting of homes, was translated as Mengikut Arus. A direct translation of “tracing” (menggaris) and “movements” (gerakan) would have resulted in “menggaris penggerakan”, which fell flat and is disconnected from context. Instead, Mengikut (“to follow”) Arus (“currents”), accurately conveys the sense of shifting and transformation.

The importance of testing waters

We wanted to ensure our modes of engagement were accessible at different levels of participation. This required us to test out prototypes and make adjustments where necessary. We were provided with a roughly 4m by 4m booth, situated alongside other exhibitors. Due to the nature of the activities, providing ample space for participants to comfortably write and reflect was important. We visualised the exhibit layout to test the orientation flow, then built a prototype in our office space. We invited Orang Laut SG to try the activities and share their feedback.

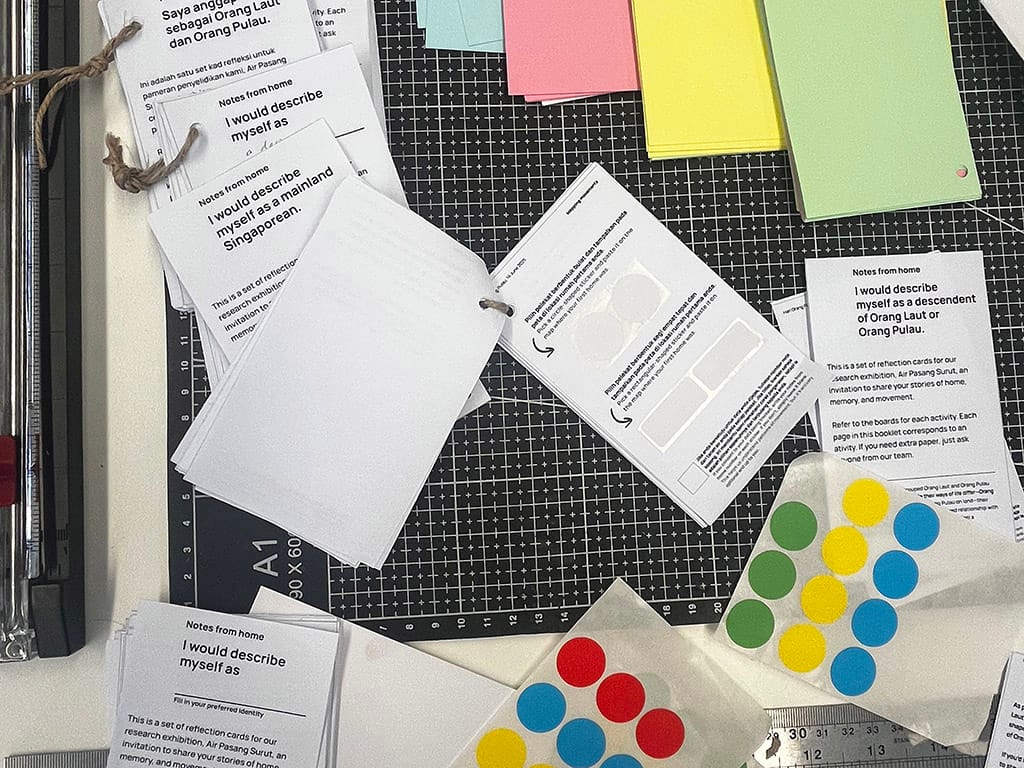

Testers received colour-coded note sets, each tagged to an identification number, to write their reflections to the exhibit’s prompts. This enabled us to trace responses based on identity groups. Some prompts were paired with photographs of the Orang Laut’s daily lives to aid memories. There were also three maps; of Singapore and the Southern islands, parts of Malaysia, and parts of Riau, where they could paste the locations of their first and current homes.

We quickly realised that it was a bit too much: our testers needed to be closely guided for us to walk through what the note set meant, and it was a lot for one to process back-to-back prompts. The note system was simplified to identity-coded coloured papers, so the data gathered would prioritise showing broader patterns over individual data tracking.

The maps however, were very helpful as they provided macro and micro views, which helped members of the Orang Pulau and Orang Laut community recognise specific islands that could not be distinguished by the eye from high zoom level maps. We also consulted the team as to whether the Indigenous island names were accurately displayed. One of our main references was from serumpun.ig, a social media curating shared Nusantara histories, which detailed names of the various kampungs and islands before urbanisation and reclamation.

Before testing, we envisioned that participants would respond to the activities in a sequential fashion. We eventually realised that open-ended exhibitions facilitate different levels of participation in a non-linear manner. In the end, we streamlined the activities to make them more intuitive. People could take part in three activities: two open-ended entry points and one mapping board for marking first and current homes.

Memories from Hari Orang Pulau

The lively chatter, wholesome exchanges, and festive music charged the air on Hari Orang Pulau. Curious visitors and onlookers were drawn to the maps of Nusantara, which organically became a storyteller’s enclave. The maps of Nusantara were the beacon of the booth; Orang Pulau and Orang Laut and non-islanders alike turned the humble 4x4m grass patch into an offbeat intergenerational space for connection, contemplation and curiosity.

Left: Orang Seletar, Jefree Salim, adorned with his traditional headdress, sharing about his relocation and tie to the straits between Singapore and Johor. Right: Griselda helping to paste a sticker of where an Orang Laut’s first and current home is located at.

There were many memorable moments where older folks would stop by, and generously share their memories and knowledge. From an event-goer proudly sharing that his wife—an Orang Laut—still practices silat gayong, to a mainlander recalling the names of the vanished kampungs on mainland Singapore, to an elder recalling owning a boat and diving for fish in his youth; these personal stories demonstrate deep-rooted connection to the land and sea, and by extension the loss of homes, traditions, and livelihoods as a result of displacement.

It was heartening to see members of the community lingering around the booth telling stories of their homes and their journeys around the region. Even though the booth was intended to be part of a data gathering effort, these tender moments of exchange and reflection were truly the glistening pearls we inherited from Hari Orang Pulau.

In the long term, we hope to build an Indigenous-centred research project with Orang Laut SG, on the environmental impacts of unquenched thirst for urban development and displacement amongst the Orang Laut and Orang Pulau, and unpack how this further affects the community’s socio-economic conditions. Air Pasang Surut was but a starting point in capturing displacement data through a participatory mapping exercise; more importantly, it was a stepping stone to building trust with members of the community.