Carrying memory through kitchen tools

How is cooking a symbol of community, memory, and cultural expression? In this behind-the-scenes article, writer Taahira Ayoob and designer Griselda Gabriele walk us through their process of crafting our latest story on natural utensils in Tamil kitchens. This story is based on Taahira’s research trip to Sri Lanka, where she spent time with local women who keep tradition alive.

Taahira: The end of 2023 was horrible for me. I got robbed of almost all my belongings on Christmas Eve in Barcelona, and had to deal with some of Spain’s painful bureaucracies in the aftermath. So when I got the news that I’d been chosen as one of Texam A&M’s media fellows to investigate culinary tours as a form of tourism regeneration in January 2024, it was the first good news of the year.

My idea was to explore the potential and possibility of offering home-cooked food made by Tamils living in Sri Lanka as part of a tourism experience in the northeast region of the country. The idea stemmed from my experience with Spice Zi Kitchen, a home-cooking experience led by my mother in Singapore, where we cooked and ate heritage dishes with guests to connect them with our culture, tradition, and history. In the last six years, my mother has grown immensely in confidence and connections, both gained from hosting and opening our home to foreigners and other Singaporeans who were curious to learn about our food.

Taahira and Mama Zi at their home, where they host Spice Zi Kitchen

Taahira: Traditional cooking practices sustain local foodways and create immersive experiences for visitors, reinforcing cultural identity and pride (P. Manikandan, 2023). With this knowledge as a foundational premise, I embarked on desk research and searched for networks on the island leading up to my trip in March 2024. During this time, I connected with Ramesh, my fixer, through a Facebook group and a friend’s recommendation. He is a community leader involved with NGOs and also works as a tour guide.

Ramesh helped line up a few interviews and explained my intentions to the women I hoped to meet. I wanted to understand what and how they have been cooking, especially after the war, with limited resources and tools.

Taahira: Before the trip, I also worked on a documentary featuring Sri Lankan Tamils in Paris, as part of a series commissioned by Channel News Asia on exploring diaspora identities in Europe. Many of these profiles had fled during the civil war between the Sri Lankan Army and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in the late 1980s to 1990s, and built a second generation of family away from the island. On the other side of the world, the war lasted 30 years, claimed over 70,000 lives, and ended only in 2009 with the death of the LTTE leader, Prabhakaran. The LTTE had been fighting for an independent Tamil homeland after decades of systemic discrimination, especially in education, employment, and daily life. I learnt, through my interviews in Paris, that those who fled rebuilt their lives and held tightly to their heritage through language, restaurants, and community events. These interviews made me wonder about those who chose to remain on the island during those years.

(From left to right) Behind the scenes of The New Locals which is a docu-series on Channel News Asia and the office of an interviewees from docu-series in Paris, a community centre supporting Tamil Sri Lankan refugees and asylum seekers.

Taahira: Prior to these experiences, I had only been to Sri Lanka once, back in 2014 with a close friend, and had never visited the northernmost province. In March 2024, I landed in Colombo and took an overnight bus to Jaffna, or Yalpanam in Tamil. Train connections weren’t running during my stay, and many locals complained that this was one reason development in the north remained sparse. My friends and contacts in Colombo, too, told me they’ve never been to the north, often citing its troubled past or lack of infrastructure.

Taahira: I stayed at D’Villa Guest House in Jaffna, where Dillon, the owner, was kind and attentive, welcomed me with breakfast and made sure I had everything I needed as a solo female traveller. He even arranged a bicycle, which I rode on my first day of rest. Yalpanam felt familiar in its heat and humidity, with tall palm and coconut trees, and the scent of incense near temples.

(From left to right) D’Villa Guest House veranda/dining area, scenes by the road in Jaffna, a rented bicycle by Palmyrah trees

I wore a salwar-kameez to blend in, but still got a few honks while cycling around.

Taahira at the Catumaram Guest House in Jaffna

The restaurants served meals that reminded me of Little India thali sets on banana leaves, dosai, chapati, uttapam, and various rice dishes.

Utthapam with side dishes

Taahira: That afternoon, I met Ramesh and we mapped out who I could speak with across the Northern Province. He advised me to approach the subject of the war delicately. Most people wouldn’t feel comfortable talking about it right away. He also mentioned that Jaffna City itself is relatively safer, while areas like Mullaithivu and Vavuniya saw heavier impacts of the war in terms of food availability, destruction, and violence. Ramesh’s bilingualism was incredibly helpful as some Eelam Tamil words differed from the Tamil I’d grown up with in Singapore. Words like “later” (paiyinthu), “mistake” (pilai), and “beautiful” (vadivaka) were slightly different from what I had learnt growing up. I was worried my Tamil proficiency would inhibit me from speaking with the local women, but my journey of speaking and cooking with them brought me closer to my mother tongue.

(From left to right) Rameshkanth, Taahira’s fixer and friend and Taahira with Asha’s daughter

Taahira: My first interview was with Asha and her mother, who live on the outskirts of Jaffna. We took a bus from the city centre and then a tuk-tuk to reach her home, which they had rebuilt after it was demolished during the war. The porch was full of banana, coconut, and moringa trees, as well as tomato vines. Her kitchen was small, with a wood fire, and the family collected rainwater from a spout at the back. I didn’t photograph or film her immediately. I waited until she felt comfortable.

I introduced myself and the project, making sure to inform them that I would be an extra hand in the kitchen, and not just a guest they had to serve.

My methodology for my interviews and research was based on Participatory Action Research, which is an approach that emphasises collaboration and participation from the women I was interviewing. To stay true to the research, I offered the idea of culinary tours to the women and listened to their feedback, worries, and interests. I made sure not to capture photos of the women directly, as this was not something most of them were comfortable with. This is where Griselda’s illustrations came in extra handy, as she managed to depict the interviewees with illustrations while keeping their identity hidden.

Griselda: As we wanted the women and the tools they cooked with to anchor the story, we start each chapter with portrait illustrations. With Taahira’s photos as reference, I illustrated the women, as well as the communities they are part of. The latter is especially important, as all the women here regularly cook together with their family members and neighbours.

Some early sketches of the women’s portraits. A Sri Lankan map was added later as suggested by our Editorial Lead, Nabilah, to help readers orient themselves and feel more connected to the locations

Taahira: Asha was unsure at first; she couldn’t understand why anyone would be interested in her cooking. Regardless, we got to work quickly, and together we made five dishes: thirrukai kuzhambu, green banana poriyal, white eggplant curry, papaya curry, vallarai varai, and kothu arasi. Through the cooking process, I could see she was in her element, being able to balance feeding her daughter, answering the phone, and cooking at the same time. While cooking, we used a variety of different tools such as the aruvmanai, solavu, and ammikal. These were items I had only seen in my grandmother’s home when I was a kid, which were notable because of how large and heavy they were.

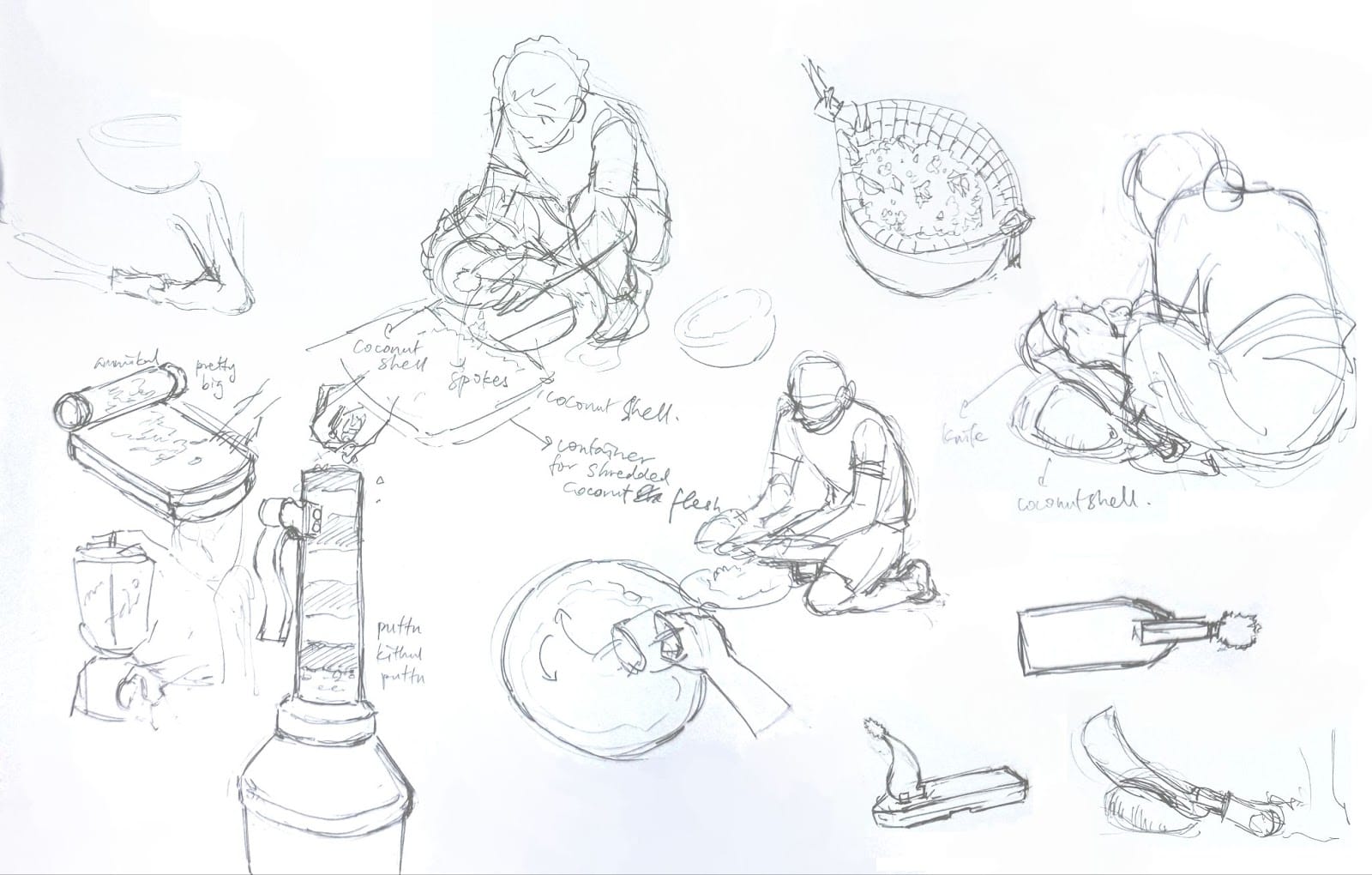

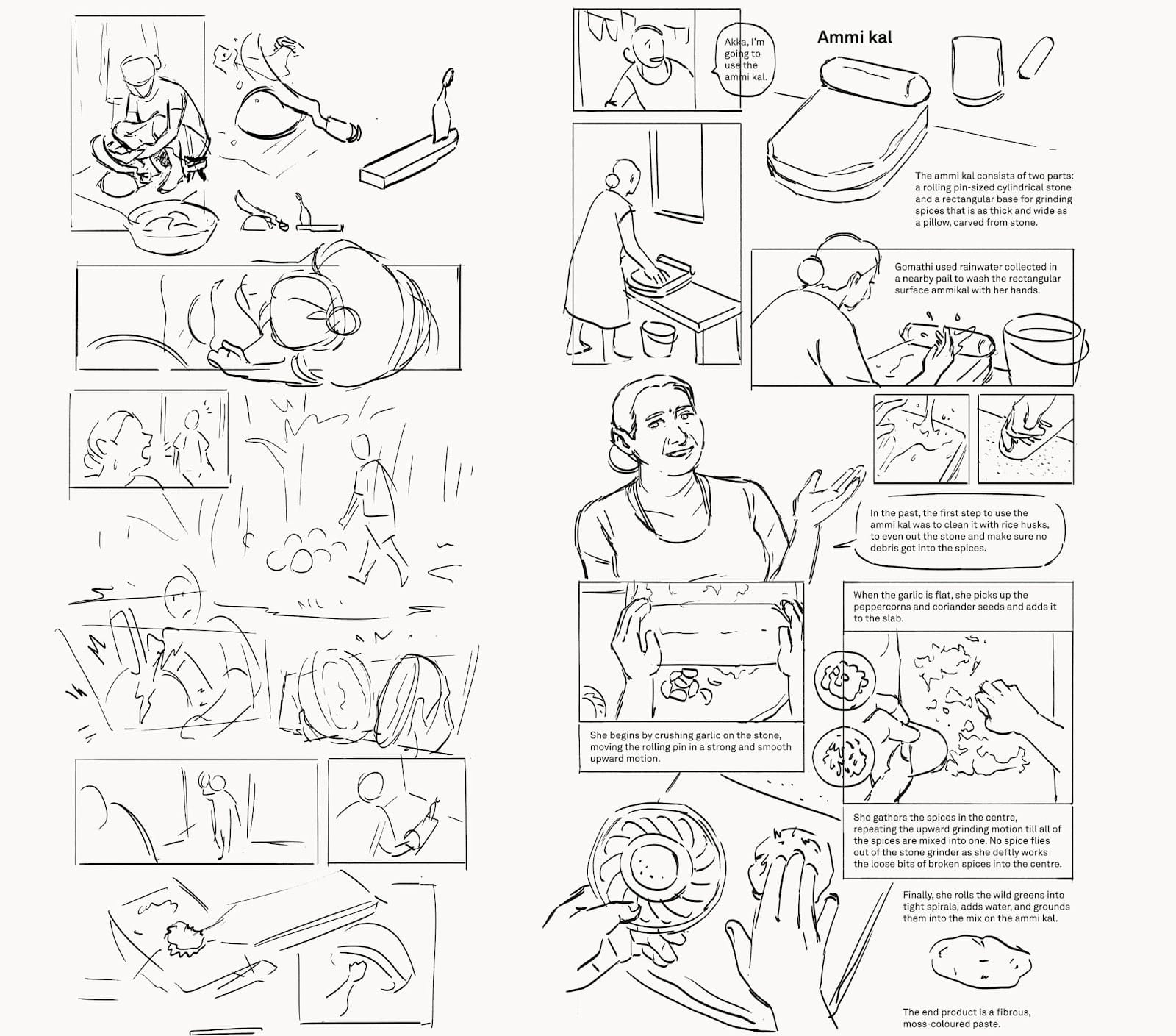

Griselda: In our story, each tool gets a comic depicting how they’re used. The women’s cooking processes are very meticulous, and we wanted to make sure to depict their amazing skills with these tools. Thankfully, Taahira wrote some vivid descriptions and took a lot of detailed photos!

Early sketches to understand how the tools are used

Griselda: All in all, these aspects were depicted for each tool:

- A description of the tool

- The women who often use them and how they collaborate with other members of their community

- Steps involved in using the tools

- Dishes and ingredients involved

The laborious cooking process also means that it’s usually a communal effort. Neighbours or family members are often called to help out, and these comics allowed us to give a little spotlight to their role.

Some comic sketches alongside reference photos used

(From left to right) Ammi kal being used, aruvamanai in use to cut stingray, aruvamani used to grate coconut

Taahira: When I explained how Spice Zi Kitchen worked and the potential of, she said, it could be possible, if the guests spoke Tamil and if they had more infrastructure for the kitchen and living space. We ate lunch on the floor, the food placed on banana leaves, with her children and her mother as Asha got ready to go to work.

(From left to right) Asha adjusting the wood for the woodfire stove in her kitchen, preparing the meal served at Asha’s house —at the centre is kothu arasi (rice), and from the at the top left moving clockwise is stingray kuzhumbu, green papaya curry, fried green banana, varai, and white eggplant curry.

Taahira: During the conversation, Asha told me about losing her crops and cattle during the war, and being caught in crossfire while pregnant with her first child. She still bears a scar on her inner thigh and remembers the bland rice porridge they had to survive on. Today, she earns an income from community work and selling homemade hair and skincare products using plants from her garden.

We stayed for about five hours. By the end, Asha was laughing with me and insisted I return to document her product-making process. I paid Asha a fee for her time and the ingredients, just as I did with the other interviewees.

After Asha, I continued to interview several others across the Northern province. Many of them taught me to cook dishes specific to their family and the times they grew up in, like puttu biryani, odiyal kool (a rich broth made from palmyrah root flour, seafood, pumpkin, local greens and chili), and aaru meenu sothi (river fish soup with pumpkin). I also reflected on the vastness of kitchen tools and the fire wood they used, that made me feel more connected to nature while cooking with them. I wondered, how would this have been in the past in kitchens in Singapore, or elsewhere in Southeast Asia?

Griselda: In an earlier version of the draft, the story ended with a comparison of traditional tools and modern tools that serve similar purposes, along with pros and cons. But as we discussed the story’s conclusion, we realised that many of these tools persist to modern day. Not only that, while the story focuses on Sri Lankan women, readers may actually have seen some of the tools in different, but familiar forms. Because of this, we decided to celebrate the common aspects between traditional tools and crafts across Asia instead.

A snippet of the story’s final visualisation, featuring different types of leaf wrappers across Asia

(From left to right) Ammikal, odiyal kool

(From left to right) Ingredients for puttu biryani, puttu biryani

Taahira: While on the bus down from Yalpanam back to Colombo, I stopped in Ella for cooler weather and to connect with upcountry Tamils, whose ancestors were brought from Tamil Nadu during the era of British colonisation to work on tea plantations. Though they were spared the violence of the civil war, they continue to face economic hardships because of low wages for tea-pickers. Yet, as with the families I met in the north, the women here took pride in feeding their families well. Gomathi, the eldest woman in the family took charge to prepare a meal rich in greens, consisting of rasam, sothi, and two types of varai for the cool weather.

(From left to right) Gomathi’s sister-in-laws at their home in Ella overlooking the tea plantations, meal prepared by Gomathi for Taahira—served on a banana leaf and on a traditional straw mat

Taahira: Originally, my interviews were focused on dishes, ingredients, and the potential for culinary tours. But along the way, I realised how vital kitchen tools were in the making of these meals. That’s what led me to pitch a story on natural utensils to Kontinentalist.

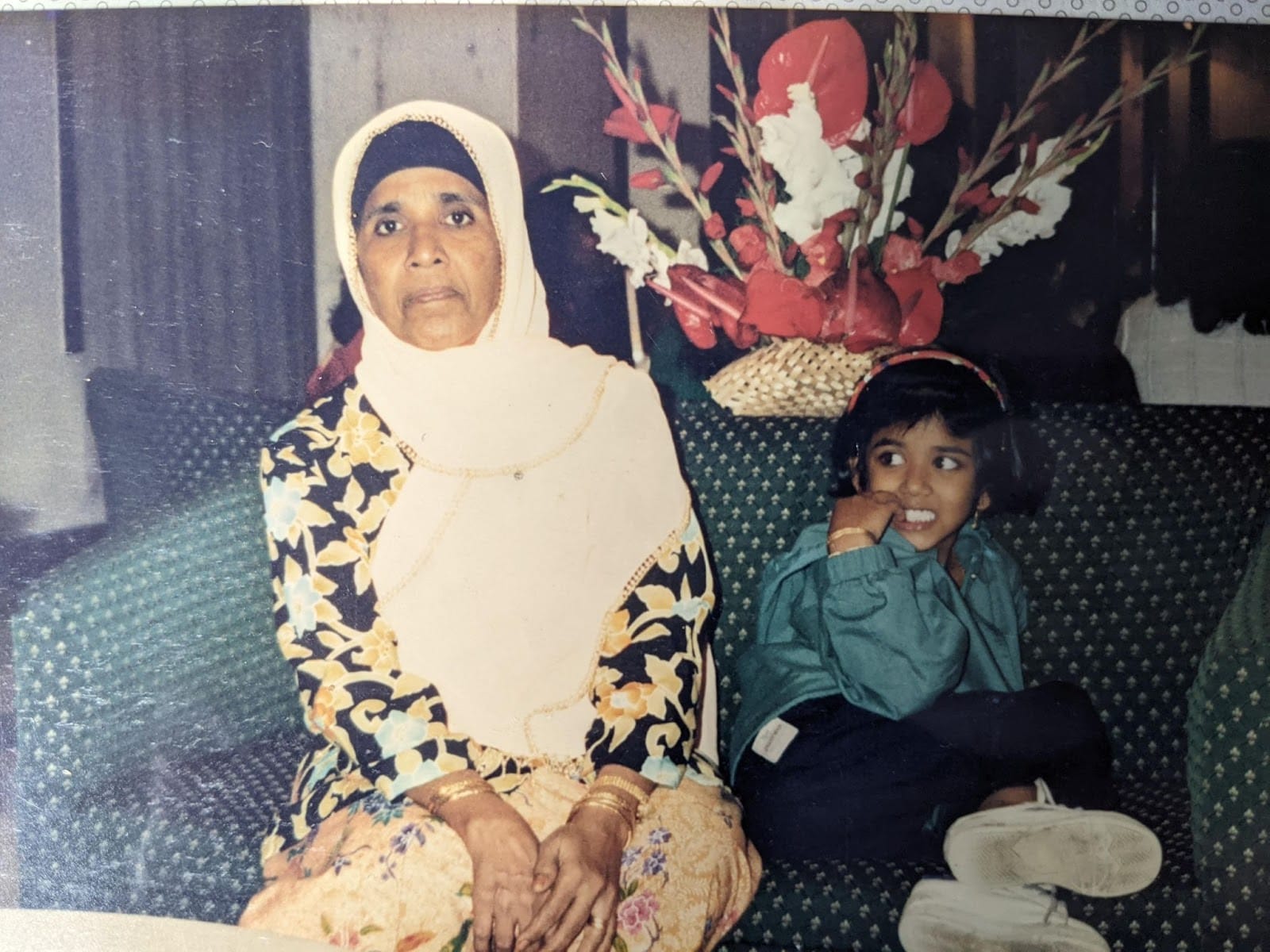

As I travelled, cooked, and spoke with these women in Tamil, many of whom were much older, I often thought of my grandmother and her journey to Singapore. My grandmother migrated from Kadayanallur, a rural town on the Tamil Nadu–Kerala border, to Singapore in the 1950s as a bride with her husband, Ibrahim. As a child, I remember visiting her spice stall in Changi Village, where she would hand-grind spices on an ammikal and insist on feeding us whenever we visited.

Maryam (Taahira’s grandma) and Taahira when she was 8 years old

Taahira: As an immigrant who arrived in Singapore by boat after travelling for 90 days, she was selective of what she brought as luggage. She brought with her, sarongs, muram, and an ulakku. The ulakku in particular was special as it was handcrafted by her brother, with “Maryam” engraved on the back.

(From left to right) Kopperrai, a bronze steamer used for idli, puttu, and kozhukattai. Ulakku, a tool used to make iddiyappam and murruku

(From left to right) Sollavu or muraum, used to separate husk, rice, lentils, grains and Taahira’s grandma and her uncle

Taahira: After Taahira’s grandmother’s passing, her tools became a topic of discussion. In land-scarce Singapore, some relatives wondered if it made sense to keep them. But Taahira’s mother, the most sentimental of her siblings, held on to some of them as reminders of her mother.

Today, at Spice Zi Kitchen and for regular meals, Taahira and her mother still use it to make murukku and idiyappam.

Ulakku used to make iddiyappam (spring hoppers) at Spice Zi kitchen

Taahira: Using these tools today at Spice Zi Kitchen is one of the ways I strive to stay connected to this lineage. Whether it's grinding spice pastes with an ammikal or using a muram to sift flour, these actions carry memory. They remind me of the hands that taught me and the tools that nourished generations. Cooking with these tools isn’t just about technique; which is often the worry around using traditional tools over modern ones. They do take time, but the process is a practice of remembering.

Mama Zi and Taahira at a Spice Zi Kitchen session

Taahira: Someday, I hope to inherit them and bring them to my current home in Barcelona. These tools are more than just functional. They hold memory, migration, and meaning, just like the women I cooked with in Sri Lanka and the many more people I hope to cook for.

References:

https://www.irreview.org/articles/the-overlooked-human-rights-problem-sri-lankan-tamils

Traditional cooking practices sustain local foodways and create immersive experiences for visitors, reinforcing cultural identity and pride” (Manikandan, 2023, p. 4).

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-51184085

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/may/18/tamil-tigers-ltte-prabhakaran-death-srilanka